“There are no first-hand contemporary sources from the time of the Revolution that mention Molly Pitcher at the Battle of Monmouth,” David Martin writes in the single most comprehensive volume on the topic.1 Only three contemporary sources from after the American Revolution mention the story of a woman crewing a cannon at the battle — and they all contradict one another on important details.

One of the two battle accounts may be a forgery, for there is no mention of the incident in the diary left behind by its reputed author, while only the “Pension Application of Rebecca Clendinin,” written in 1840, uses the name “Molly” at all, naming her as “Captain Molly.” None of these three sources is more than a few sentences in length. Martin’s collection of primary sources thus starts at page 1 and ends at page 5; his author photograph is on page 329.

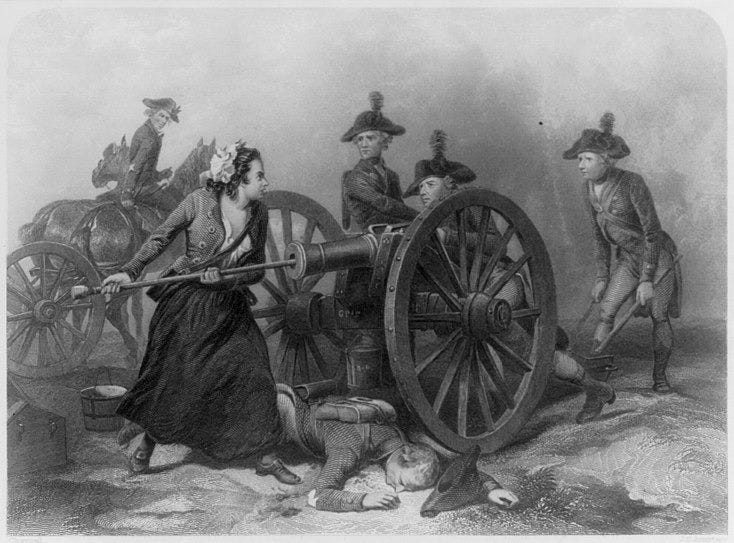

Everything on the other 324 pages is about secondary sources — history as written by people who were not at the battle, or who were not even alive during the Revolutionary War. The closer one looks at the story of Molly Pitcher, the more her image fades from reality into myth. If you ask me, the least-likely part of the story is that her pitcher or canteen carried water for thirsty cannoneers, for the sponge-end of that ramrod in her hands tells a different story.

The name “Moll Pitcher” was “in common parlance at the time,” Martin writes, but Captain Molly did not become Molly Pitcher until 1837. The first use of the name in association with the Battle of Monmouth was a newspaper article in the New Brunswick Times. The original is now lost, but it was reprinted in the New-Jersey State Gazette. Written after the election of President Martin van Buren, Andrew Jackson’s handpicked successor, when the WHIG ticket had been split four ways, it is imbued with the spirit of contemporary political partisanship.

For the benefit of that class of full-grown children and embryo patriots who talk much more of New Jersey chivarly about election times than they ever learned, or likely [sic] to learn from history, it may be proper here to add what every New Jersey boy should know — that at the commencement of the Battle of Monmouth, this intrepid woman contributed her aid by constantly carrying water from a spring to the battery where her husband was employed as a cannonier in loading and firing a gun. At length he was shot dead in her presence just as she was leaving the spring; whereupon she flew to the spot — found her husband lifeless, and, at the moment, heard an officer, who rode up, order off the gun “for want of a man suffciently dauntless to supply his place.” Indignant at this order, and stung by the remark, she promptly opposed it — demanded the post of her slain husband to avenge his death — flew to the gun, and, to the admiration and astonishment of all who saw her, assumed and ably discharge the duties of the thus-vacated post of cannonier to the end of the battle! For this sterling demonstration of genuine WHIG spirit, Washington gave her a lieutenant’s commission upon the spot, which congress afterwards ratified. And granted her a sword, and an epaulette, and half-pay, as a lieutenant for life. She wore the epaullette, received the pay, and was called “Captain Molly!” ever afterwards.

The sword, uniform coat, epaulette, and half-pay as a lieutenant are curious echoes of a Napoleonic heroine, Agustina de Aragón, who fired a cannon during the 1808 siege of Zaragoza and became a propaganda figure.

“I rather incline to the theory that the Monmouth story was inspired by the story of the Maid of Saragossa,” historian Jeremiah Zeamer wrote in 1909.2 “The two have marks of resemblance, viz: the Maid was a water bearer, as was also the Monmouth woman; the Maid was 22 years old, which, according to most writers, was the Monmouth woman's age; the Maid had a lover who fell at the gun and at Monmouth the woman had a husband killed.”

Just as her legend had been burnished to promote the new Spanish nationalism, Molly Pitcher too seems a constructed figure, a myth intended to inspire a nascent national spirit.

Molly has usually been described as plain or even homely; New Jersey historians John W. Barber and Henry Howard called her “a female of masculine mold” in 1844. However, George Washington Parke Custis, the adopted stepson of George Washington, called her “the Amazonian fair one” in his 1843 essay “The Battle of Monmouth.” Born three years after the battle, Custis could not remember a time before American independence. He was the first writer outside New Jersey to mention Molly Pitcher in print.

According to Custis, she was now “a matross [assistant gunner] in [Col. Thomas] Proctor’s artillery” who “was serving some water for the refreshment of the men” when her husband, who was manning the gun, was struck in the head and killed instantly. The remaining gunners fired the loaded cannon at Molly’s direction.

“Then entering the sponge into the smoking muzzle of the cannon, the heroine performed to admiration the duties of the most expert artilleryman, while loud shouts from the soldiers rang all along the line, the doomed gun was no longer deemed unlucky, and the fire of the battery became more vivid than ever.” And then everyone clapped.

Custis has contrived a speech for Molly. He writes that she was presented to Washington, who gave her “a piece of gold.” In his account of “Washington’s Headquarters,” also written in 1843, Custis writes that she “was always received with a cordial welcome at headquarters, where she was employed in the duties of the household,” such as laundry.

Still, Molly “wore an artilleryman’s coat with the cocked hat and feather, the distinguishing costume of Proctor’s artillery.” Custis offers a humorous anecdote involving her petticoats in battle. It seems a bit much because it is almost certainly false.

“There is no evidence of any ‘Irish Molly, wife of gunner’ being at Monmouth nor evidence of any woman there ‘being complimented after the battle,’” Zeamer writes. “Washington was in no humor of giving compliments at that battlefield. It is there he is alleged to have sworn with a big D at General Lee for trying to have the army defeated.”

Furthermore, “Washington could not confer the title of Lieutenant on any one nor order half pay. That was the province of Congress and Congress did not do either for any woman for any action at Monmouth or elsewhere.”

Custis also painted a scene of Washington at Monmouth (see above). Damaged by the way it was stored during the American Civil War, the painting has been restored and is on display at the Robert E. Lee home in Arlington, Virginia. Although Curtis painted her at the margin of the canvas, this work of art clearly inspired the artists and writers who retold the story of Molly Pitcher thoughout the rest of the 19th century, transforming the local New Jersey legend into an all-American myth.

In 1848, Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, the widow of Alexander Hamilton, recalled meeting “Captain Molly” a total of three or four times. In her telling, Washington made the “stout, red-haired, freckle-faced young Irish woman named Mary” a sergeant, Martin writes. However, Mrs. Hamilton had confused the purported Molly at Monmouth with “Captain” Molly Corbin, a woman who actually fought at the Battle of Fort Washington in New York during 1776 and did hang around Washington’s headquarters after.

When her husband John was mortally wounded, Corbin took his place as matross until she was seriously wounded herself by grapeshot. Molly Corbin is who Mrs. Hamilton met at Newburg in 1782 and misremembered as Molly Pitcher, Martin explains. “The confusion is not surprising, since both women were known as ‘Captain Molly’ and both were noted female combatants who served in the artillery.”

The error in Benson Lossing’s 1848 interview with Hamilton’s widow was immortalized in his 1851 Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution, “which transmitted the mistake to numerous other later authors.”

Similar confusion, and possibly outright fabrication, explain how Rev. C.P. Wing misidentified Mary Hays McCauley of Carlisle, Pennsylvania as Molly Pitcher in 1878. According to Wing, she had been born to a German family as “Mary Ludwig” in Trenton, New Jersey. However, the family bible that supposedly confirmed this identification is lost, if it ever existed. Other writers soon named her birthplace as Allentown, New Jersey.

A rumor that she had died of syphilis, and had been known locally as “Dirty Kate,” crept into some versions of the story. At the time, that sort of death was considered melancholy, and therefore poetic, even if scandalous. Writers also began to confuse the siege of Fort Clinton with the Battle of Monmouth, putting her at both battles.

Yet the case for McCauley is “built on a deck of cards,” Martin writes. “Each piece of evidence … has a weakness or loophole, and there is no clear-cut ‘smoking gun’ to confirm her case.” The primary sources left to us “are particularly weak.”

Newspapers in New York and Washington, DC that reported her pension “were totally confused about what distinguished service Mary Hayes McCauley was supposed to have performed,” stating that she had been “‘wounded at some battle, supposed to be Brandywine, where her sex was discovered.’” Martin concludes that Molly Pitcher is likely a composite character created from real women of the American Revolution.

Erected in 1916 and sculpted by Swiss immigrant J. Otto Schweitzer, her statue in Carlisle, Pennsylvania bears the composite name “Mary ‘Ludwig’ Hays McCauley.”3 Schweitzer has a canteen on her left hip, slung over her right shoulder, but no pitcher. Modern reference works also display historical ambiguity. For example, “Molly’s life prior to the Revolution is still a mystery,” the 2004 Encyclopedia of New Jersey says.4 “Several towns in New Jersey claim to be her birthplace, and a number of possible maiden names have been suggested, but the truth has yet to be uncovered.”

We are unlikely to ever have the ‘real’ name of Molly Pitcher because she is less real than she ever was. She has faded from historicity, though not history.

American women led the new Spiritualist movement that was reshaping religion. Industrialization and modernization were changing the way women lived. Early feminists were just beginning to write and organize for their own political suffrage. It was called the Progressive Era.

In their book History of Woman Suffrage, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage and Ida Husted Harper used stories of women during the American Revolution to argue for the political independence of women and decry the legal backsliding of women’s rights in law after the conflict. Molly Pitcher has endured because American women wanted a symbol of female patriotism to restore the project of female emancipation.

Historian James Hutson writes that by “accepting (in many cases unwittingly) the formulations of Mrs. Stanton and her assistants, today's writers on women in the Revolutionary era are suffragists, purveying as history the propaganda of another age.”5 It would be too easy to dismiss the myth of Molly Pitcher as a sheerly ideological project, however, for the authors of History of Woman Suffrage cribbed another writer — a woman, but not a feminist.

The Women of the American Revolution, by Elizabeth F. Ellet, was published in three volumes between 1848 and 1850. In the latter year, Mrs. Ellet produced a Domestic History of the American Revolution, an abridgment of the larger work, which also amplified it by including fresh material. That Mrs. Ellet's work appeared in 1848, the year of the first Woman's Rights Convention, seems to have been coincidental, for she was not a disciple of the fledgling movement.

“Ellet's works are the data banks from which subsequent writers have retrieved their information about Revolutionary women and events,” Hutson explains. “The authors of the History of Woman Suffrage were heavily indebted to her, as were Harry Clinton and Mary Wolcott Green, whose three volume study entitled The Pioneer Mothers of America (1912) is, at times, a paraphrase of Mrs. Ellet.”

Whereas History of Woman Suffrage “has all the liabilities of a book written by leaders of a movement in the heat of battle,” it is “clearly the major source of the views of current writers of women's history” in 1975, when Hutson wrote his essay.

At the time those early American feminists wrote their book, however, women were in fact being excluded from military history. Indeed, the militaries of the modernizing world were admitting fewer women to battle than they had in ages.

“When military history emerged during the latter part of the nineteenth century, armies were not what they had been even a few decades earlier,” Barton Hacker writes.6 “In particular, the centuries-long process of bringing military support services under direct military control had been completed.”

As a result, “women, who had been an integral part of that world for at least four centuries” — what historians call ‘the modern period’ — “vanished in the change.” Professionalization of arms and the technologies of the age were conspiring to replace or exclude women from their former roles in military camps.

Army sizes became enormous. Railroad tables came to dominate logistics planning. Women, and moreover children, had to justify the rations assigned to them on voyages. Printed tickets, telegraphed orders, and other management technologies limited passengers during army transport.

Florence Nightingale demanded the professionalization of nursing services, the predominant volunteer role of women who had accompanied armies across history. While ‘women’s work’ “was no less useful in an army camp than a peasant village,” Hacker writes, it was rendered less necessary by all this ‘progress.’

Victorian morality played a role, but it was also the age of scientific hygiene. Hoping to reduce troop losses to venereal disease, British generals limited the number of women they brought to the Black Sea during the Crimean War, while the French, who had been infamous fornicators across Europe since the Middle Ages, brought none of their own women.

The Contagious Diseases Acts of England during the 1860s “equated camp follower with prostitute; in the name of controlling veneral disease and guarding the men’s health, army and navy women, save the handful who remained [authorized], lost what legitimacy they had left,” Hacker writes.

Women “had come to seem not merely useless but harmful” to military order. Their “absence from late nineteenth-century armies debarred them from military history in its formative stages, and ever since has obscured the meaning of their presence in other armies at other times,” Hacker concludes.

Molly Pitcher most likely began as a figure of popular oral history, a local New Jersey legend. Combined with a case of mistaken identity in which Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton likely influenced George Washington Parke Custis, the composite character of Mary ‘Ludwig’ Hays McCauley has always distracted from the historical woman, Molly Corbin, who actually fought in a battle and was left an invalid by her wounds.

Which brings us, finally, to the pitcher.

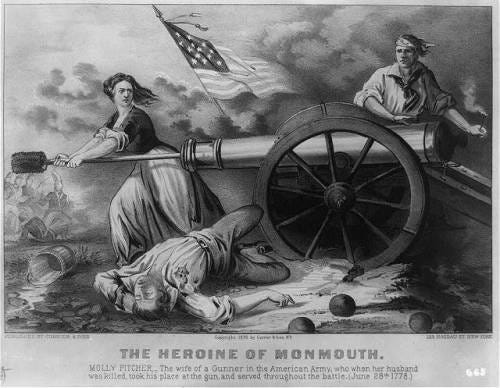

Pitchers are for quenching human thirst. Sometimes Molly Pitcher is said to carry, or is pictured carrying, a canteen with which she is supposed to be quenching the thirst of soldiers.

But Revolutionary War troops carried their own canteens, and while one woman might take ten canteens to a spring to supply a whole squad at a time, one woman with one canteen is an extremely inefficient water distribution system.

In the real world of things that really happened, Molly Corbin used a pail or bucket, likely carrying them two at a time, in order to quench the thirst of gun barrels. Almost alone among historians, John Todd White noted in his 1977 essay that Molly was not bringing water for the men to drink, but to swab the cannons.7

As demonstrated here in the very first minute of this Revolutionary War artillery reenactment video, a gunner or matross uses the “sponge” at one end of the ramrod — the item that Custis mentioned in his text — to do the swabbing. It is the very first step in every firing drill.

Clearing any burning embers from the barrel, as well as the residue of the black powder charge and any cartridge material left inside, renders the gun safe to reload with gunpowder.

As the video shows, the swab sponge comes out of the gun barrel absolutely covered in muck. To avoid creating buildup in the barrel, the sponge has to be rinsed before it can go back into the cannon.

The water in the bucket thus had to be replaced a few times over the course of a day-long battle, so the matrosses spent some part of any battle fetching fresh buckets from whatever convenient water source was at hand. As demonstrated above in the video and shown in the Armytage-Chappel depiction above, the pail or bucket was usually hung from a hook under the carriage for easy use.

The story of ‘Molly Pitcher’ never made sense. Molly Corbin’s story has always made perfect, well-documented sense. The story of Molly Pitcher has changed many times, while Corbin’s story has never changed at any point.

The real Molly carried buckets or pails of water, not because men were thirsty, but because the guns were thirsty. In the heat of battle, the real Molly took the ramrod from the hands of her dead husband and worked the gun in his place until she was wounded by British counterfire.

Molly Corbin was a real woman and she was brave. She ought to be enough, yet only the myth, born of mistaken identity, has ever rated a statue.

Previous essays in this series:

The Resistance of Agustina de Aragón and the Birth of Spanish Nationalism

I am a huge fan of siege art, and all my favorite painters know how to use fire. This exquisite scene has sparks in the background, a slow-burning matchcord on the linstock, and a flame in the belly of Agustina Raimunda María Saragossa Domènech, known as Agustina de Aragón. Spanish artist Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau Nieto portrays

Martin, David G. A Molly Pitcher Sourcebook. Longstreet House, 2023.

Zeamer, Jeremiah. “Irish Molly Pitcher.” The American Catholic Historical Researches, New Series, Vol. 5, No. 4, October 1909, pp. 379-382.

Anonymous. “The Mollie Pitcher Memorial.” The American Magazine of Art, Vol. 9, No. 1, November 1917, pp. 30-31.

Lurie, Maxine N.; Mappen, Marc, editors. Encyclopedia of New Jersey. Rutgers University Press, 2004.

Hutson, James H. “Women in the Era of the American Revolution: The Historian as Suffragist.” The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress, Vol. 32, No. 4, October 1975, pp. 290-303.

Hacker, Barton C. “Women and Military Institutions in Early Modern Europe: A Reconnaissance.” Signs. Vol. 6, No. 4, Summer 1981, pp. 643-671. The University of Chicago Press.

John Todd White. "The Truth About Molly Pitcher." in The American Revolution: Whose Revolution? edited by James Kirby Martin and Karen R. Stubaus. 1977.