World War BC? On Tollense, Troy, And The Deep History Of The Professional Soldier

A Bronze Age battlefield from Homeric time, but in Germany: REPOST

Originally posted two years ago. New content will resume next week.

“Over 10,000 human bones were found. This is the largest series of human remains that we have from this period in this region,” archaeologist Detlef Jantzen told Deutche Welle in 2017. Painstaking digs of the prehistoric battlefield at Tollense, Germany had by then revealed “a whole series of bronze weapons, such as lances, arrowheads and knives … a few wooden clubs which were used for battle as well as — and this is also remarkable — the remains of about five horses. Even though it's unclear exactly how many there were, it does show that horses died on that battlefield.”

Forget about shock cavalry tactics, though. Radiocarbon dating has placed the battle sometime around 1250 BC and Assyrians bred the first combat-ready riding horses five centuries later. As no wheels have been identified at the battle site, we can rule out the presence of chariots, leaving logistics, leadership, and messaging as a more likely set of explanations for the presence of horses. Five animals among what appear to be 130 dead men (they are all men) is consistent with primitive armies simply using pack horses. The word “primitive” can be contentious; in the context of polemology, it merely means the original state of warfare. Featuring a mix of Stone Age and Bronze Age weapons, Tollense is a window on the late Neolithic military (r)evolution, horses and riders included.

This was a battle between armies, an event in a larger conflict. “If we excavated the whole area, we might have 750 people. That’s incredible for the Bronze Age,” Jantzen told the magazine Science in 2016. “Twenty-seven percent of the skeletons show signs of healed traumas from earlier fights, including three skulls with healed fractures.” Jantzen “and [Thomas] Terberger argue that if one in five of the battle’s participants was killed and left on the battlefield, that could mean almost 4000 warriors took part in the fighting,” Andrew Curry wrote. Carried out between 2009 and 2015, the excavation was pronounced a “smoking gun” that Homeric battles were common in the Bronze Age. It happened around the same time that the Bronze Age ‘collapsed’ in the Mediterranean, where Egyptian propaganda describes a similar hodgepodge army of ‘sea peoples.’ If Tollense is a smoking gun, then it points to the stunning possibility of a primitive ‘world war’ over bronze.

To be clear, there is no evidence to suggest that Tollense and Troy and the ‘sea peoples’ are all part of one single conflict between grand alliances located at great distances, though that could make exciting fiction. Rather, these events may be linked in cascade by the primitive metal economy. Demand for bronze could have exceeded supply for any number of reasons, including wars that cut off long-distance trade routes. Armies then set out to obtain the bronze that made their existence possible.

Kingship had emerged in this world; kings wear crowns; crowns are made of metal. The new, young ‘metal economy’ was vulnerable to shocks and so were the primitive states those kings ruled. Perhaps the armies outgrew their kings.

In “Connected Histories: The Dynamics of Bronze Age Interaction & Trade 1500-1100 BC,” a 2015 article in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, Kristian Kristiansen and Paulina Suchowska-Ducke lend credibility to this hypothesis. “The Bronze Age was the first epoch in which societies became irreversibly linked in their co-dependence on ores and metallurgical skills that were unevenly distributed in geographical space,” they write. Evidence of a long-gone causeway or bridge structure at the center of the battlesite shows that this was a linked world. “Access to these critical resources was secured not only via long-distance physical trade routes, making use of landscape features such as river networks, as well as built roads, but also by creating immaterial social networks, consisting of interpersonal relations and diplomatic alliances, established and maintained through the exchange of extraordinary objects (gifts).”

New forms of organised transport had to be developed, both at sea and on land, as well as political alliances and confederations that guaranteed the safety of traders and their companies. A stop in supplies would mean severe long-term economic and political consequences, and therefore had to be avoided. Consequently we see the emergence of new forms of stable long-distance alliances and confederacies.

“There is no doubt that, in spite of constant competition, hostility, and military conflicts, all city-states were linked to each other within wide-ranging trading networks.” “During the Middle Bronze Age, 16th–13th centuries BC, the entire European continent was thus integrated into a full Bronze Age economy.” Go ahead and imagine Game of Thrones: “Dynastic marriages between chiefdoms/kingdoms along the route have long been demonstrated archaeologically.” Enough links form a chain. Displaying all the “special behavior and ettiqutte in leaders of warrior societies,” the elites of the period all knew about one other, even if they did not know one another on a personal basis.

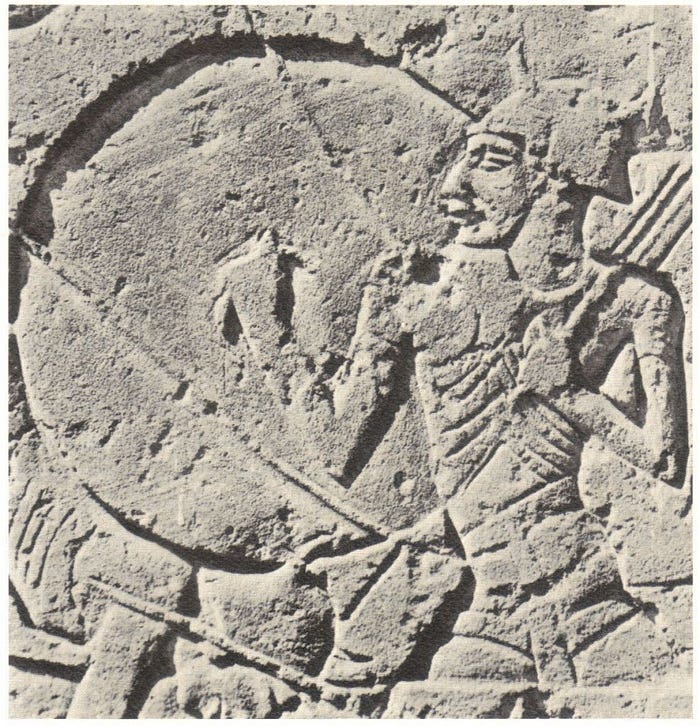

The authors mention the mysterious Terramare Culture of the Po Valley, which seems to have left their homeland at about this time and may have formed part of the seaborne collection of warriors that reached Egypt. Indeed, they may have come looking for work. “Warriors also became widely sought after as mercenaries in the eastern Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age from the 15th century onwards, as is well attested in texts and on stelae, not least in Egypt,” they write. “It explains how new sword types could spread rapidly from the Mediterranean to Scandinavia probably within a few years. Thus the combination of trade in metal and possibly in arms, as well as travelling warrior groups and their attached specialists, created an interconnected ‘globalised’ world without historical precedent.”

Weapons recovered by archaeology show the connection. “Two distinct sword types connect southern Central Europe and South Scandinavia during the 15th–14th centuries BC: the full-hilted sword with octagonal hilt, and the flange-hilted sword,” Kristiansen and Suchowska-Ducke explain. “These were supposedly linked to two different types of travel: trade and mercenary, but with obvious overlaps and modes of collaboration between them.” After 1500 BC, metal wealth from the Meditteranean shows up in Scandinavia, likely exchanged for amber, as if a trade monopoly was operating.

Europe and the Aegean during the 15th–14th centuries BC shared the use of similar efficient warrior swords of the flange-hilted type, as well as select elements of shared lifestyle, such as campstools. Linked to this are also tools for body care, such as razors and tweezers. This whole Mycenaean package, including spiral decoration, was most directly adopted in South Scandinavia after 1500 BC, creating a specific and selective Nordic variety of Mycenaean high culture that was not adopted in the intermediate region. This could hardly have come about without intense communication and practice by travelling warriors or mercenaries.

The authors cite evidence of frequent long travels from southern Germany to Jutland. Along with metals and horses and amber, there would have been a human traffic in slaves. As a result of all this mixing, the precise origin of the armies at the Tollense site cannot be identified. The dead came from all over the place. Helle Vandkilde of the University of Aarhus told Science that "it's an army like the one described in Homeric epics, made up of smaller war bands that gathered to sack Troy" less than a century later. “That suggests an unexpectedly widespread social organization … To organize a battle like this over tremendous distances and gather all these people in one place was a tremendous accomplishment."

We can know this because the wet alkaline soil at Tollense is good at preserving human remains. Archers used a mix of stone and metal points in the battle. Although fewer stone points have been found because they do not show up on metal detectors, the marks they leave on bones are distinct from the diamond-shaped injuries left by bronze heads. Both stone and metal weapons display standardization, the hallmark of military administration.

This world was associated with the arrival of swords in human hands as well. In “The Birth of a New World: Barrows, Warriors, and Metallurgists,” archaeologist Przemysław Makarowicz shows how the so-called Tumulus culture, associated with individual graves and grave goods including weapons, saw the first use of swords as burial items. During the second millennium BC, men and women both received spectacular burials, but only males were buried with swords. This development correlated with the dissemination of solar cults around harvests and the appearance of new elites.

Makarowicz sees “the emergence of a new social structure” that “took place over the course of several generations and involved the gradual dissemination of a certain lifestyle and the ideology that ‘fueled’ it.” We cannot see this ideology in archaeology, only infer its presence. New hierarchies emerged in death. “Some members of this community were buried with spectacular grave goods of bronze, gold (weapons in particular), amber, and glass. The items indicated the gender of the deceased, their social role, status, and sometimes also group membership.”

Further information about these proto-princes is available in “Princes, Armies, Sanctuaries - The emergence of complex authority in the Central German Únětice culture,” a 2019 article by Harald Meller in Acta Archaeologica. “The Circum-Harz group of the Central German Únětice Culture (2200-1600 BC) was a highly stratified society, which arose from the merging of the Corded Ware and Bell Beaker Cultures,” he writes.

This process was advanced by princes who established their legitimacy as rulers on symbolic references to both cultures as well as on newly created traditions and historical references. Their power was based on armed troops, which appear to have been accommodated in large houses or longhouses. The hierarchical structure of the troops can be determined by both their distinctive weapons and the colours thereof.

Judging from the gold found in his barrow at Bornhöck, “the prince of the Dieskau territory commanded the largest army and occupied a dominant position,” after which “the process of merging … begun by 2300 BC … was more or less completed by 2050 BC.” Moreover, the contents of princely longhouses display “the possible proof of military units, the existence of which can be deduced from the numerical proportions of distinct weapon types in hoard finds.”

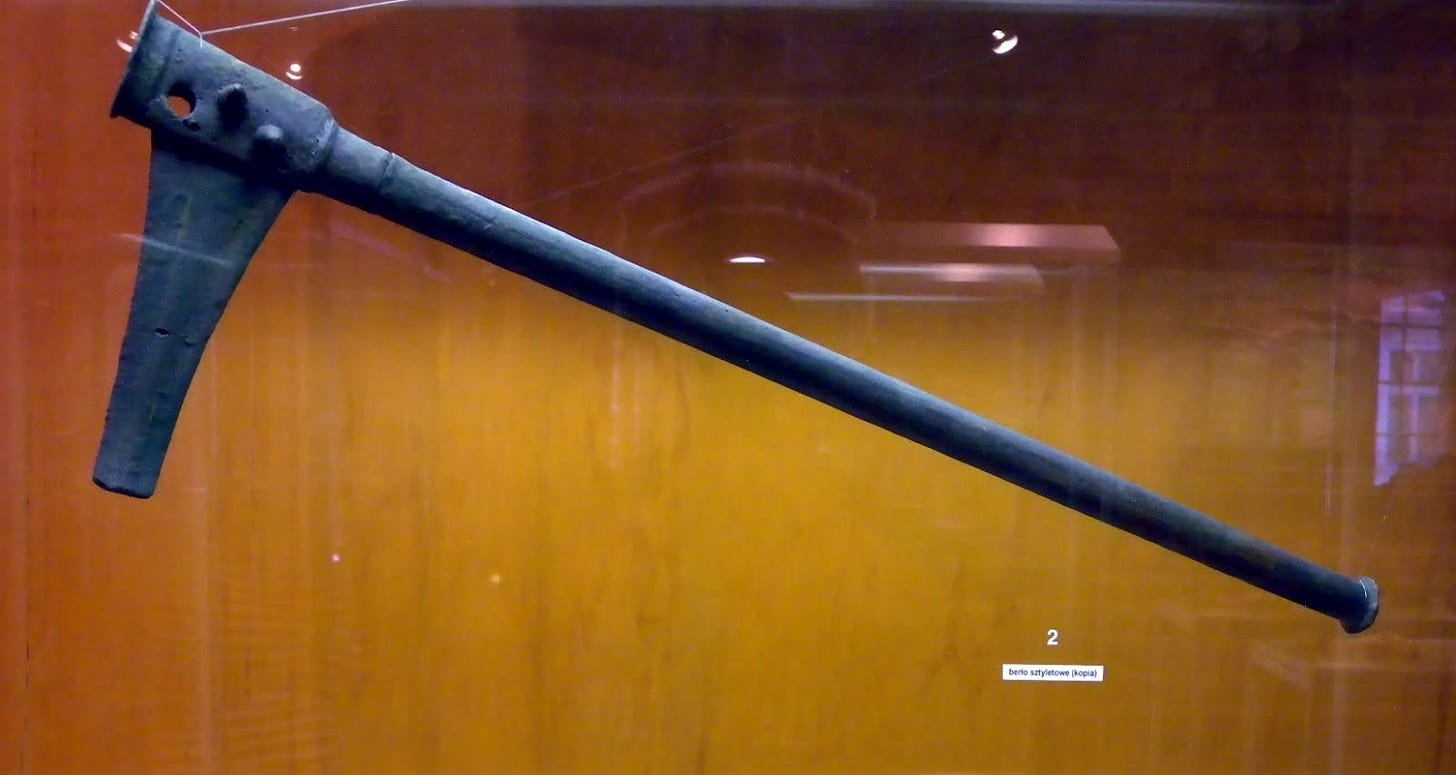

These numerical ratios, then, indicate a hierarchization of weapon types. The 1,178 axes from the Circum-Harz hoard finds account for the bulk of the weapon. These are complemented by 26 halberds, 18 daggers, and eight ribbed double axes. The implication of the large presence of so many axes should not be underestimated, because precisely the capacity for serial production based on bronze casting may well have constituted one of the main drivers of social hierarchization. Serial production is moreover suggested by chemical analyses; the metal composition in the hoards is largely homogeneous. This would not be the case if warriors had obtained or produced their axes individually.

Most of Europe cast their weapons with reusable stone molds. In Scandinavia, where the lost-wax method was used, metal weapons show less standardization. Still in use, stone weapons visibly began to imitate the new metal weapons as soon as they appeared, according to Julie Rosemary Wileman.

Metal weapons, shields, and armor were first and foremost status symbols. Swords in particular were prestige items, but shields, helmets, and armor all followed similar development tracks. At first, people used natural materials, such as wood and leather, which rarely survive in archaeology. Metals only gradually replaced these materials, appearing alongside them in battle well into historical time. As generations passed and population grew, metal became a requirement of the bourgeoning warrior class (‘real warriors wear bronze’). In a word, bronze became aspirational. Because the number of young, status-hungry males kept growing, the market demand for metals would always outstrip supply, over time — a Malthusian resource trap.

This world of newly-invented ‘wealth’ was increasingly organized by inheritance. In her 2014 book Warfare in Northern Europe Before the Romans, Wileman says that “it seems likely that ownership of metal tools was restricted in the early period to particularly important or wealthy individuals.” Because there are high-status children in some barrows, “we must be looking at a society where status can be inherited rather than earned, as the younger people and children could not be reasonably be expected to have gained respect through leadership or martial successes.”

Armies served these princes. Meller describes a typical military unit centuries before the battle of Tollense. “It would appear that the common soldiers themselves were only equipped with axes and commanded by halberd-bearers at a ratio of 1:45, by dagger-bearers at a ratio of 1:65, and by bearers of the ribbed axes at a ratio of 1:150,” Meller writes. Any military historian will recognize the platoon leader with the halberd, the section leader with the dagger, and the company commander with the ribbed axe. As Pablo Picasso exclaimed upon viewing the cave art at Lascaux in 1948, “we have invented nothing!”

Meller applies Max Weber’s definition of the state and finds much that fits in early Bronze Age Germany. This is not surprising. Any army requires a society. Most of the region had a population density of around five people per square mile at the beginning of the period, but population increased locally as the amber economy brought wealth, a brand-new invention, along with inequality, its cousin. Communities grew large enough to need protection.

Large quantities of amber from the North were transported to the Únětice territory, particularly to Bohemia but also to Central Germany, mainly during the Bz A2a phase (2000-1775 BC). From here, the amber was passed on to the southern neighbouring cultures in substantial volumes. It was thereafter confined to these cultures and only rarely transported to distant regions. These rare long-distance contacts likely represented special forms of exchange, such as princely gifts, given that amber occurs mainly in finds linked to high-ranking social contexts, e.g., the circular burial site B at Mycenae, Greece.

Humans always trade and fight with the same neighbors, occasionally even doing both at the same time. These reciprocal relationships are visible in the records of civilizations that have survived the Bronze Age, such as Egyptians and Ugarits and Hittites. While we cannot see them as text in Germany around the time of the Battle of Tollense, it is safe to assume that similar arrangements existed along this ‘amber road’. Artifacts found in the British Isles “demonstrate major trade links down the Thames to continental Europe,” Wileman says. These connections were already old and speak to long-term contacts.

Yet Wileman writes that amid all the hoards and barrows, during the Bronze Age “there also seems to have been a rise in the readiness for war — an increase in weapons production and iconography, new forms of defence sometimes imported from the Mediterranean, and relocation of settlements with an eye to defence all occurred.” She cites the example of Los Millares in southern Spain. “All across Europe, fortifications were being erected, in a number of different forms,” she explains. “Massive efforts were expended to create some of these — thousands of man-hours, thousands of trees cut down, hundreds of thousands of cubic metres of soil shifted. People clearly saw a need for protection right across the continent.”

After all, there were armies abroad. Distinctive horned helmets seem to have developed in Germany and become popular in the Mediterranean. Swords travelled from the Mediterranean to Scandinavia on the belts of soldiers. A generalized warrior culture is visible across the Old World. Unlike the cultures of prehistoric warfare, in which all men were warriors, violence was now a profession, with a new set of values defined by rulers and denominated in metal. Warriors were now soldiers.

Casualties recovered at Tollense that fell into the marsh, and thus escaped posthumous robbery, bore rings of tin on their wrists. Far less common than copper, tin was the more expensive metal in bronze. These rings may have been a form of payment to warriors before the battle. If the battle involved a trade caravan, as some researchers suggest, then the caravan guards wore the most valuable trade items in it.

Scattered more than a mile along the river, the dead of Tollense were not fighting in some remote location, either. The area was inhabited, an “open woodland at the time these people died, but close enough to farmland where cereal crops and flax were growing for the pollen from these crops to have spread,” Wileman says. Many of them had come a long way, however, for “some of them had eaten millet, a crop not often found in northern Germany in this period, and there were also finds of bronze pins that are of a type usually found 400 kilometres to the southeast of Tollense.”

Finally, the horses are yet another prestige item. Equestrian classes have always added complexity to the social structure of armies — that is, the mounted warrior costs more than the foot soldier because of his horse. This affects tactical evolution and results in argumentation among us moderns.

For instance, Wileman takes issue with the argument that “without proper stirrups, it is not possible to fight from horseback with spears or swords.” Instead, she says, “a padded and contoured cloth or leather saddle can perfectly well support a rider securely enough to allow him to throw a spear or wield a sword,” though such items will not have survived the ages. This is true, but it begs the question of who provided these specialized constructions to the primitive cavalry rider. Every item specialized for horses makes the mounted soldier more expensive than the foot soldier, who wears all the same armor and weapons.

Across Europe, where pasturage was premium and horses were quite valuable, chariot riders dismounted in order to fight. It is reasonable to suggest that mounted fighting would also have been relatively uncommon in primitive battles like Tollense, that the horse was mainly a form of transportation for prestige warriors.

Tollense itself lends some credence to this view. Rather than a massacred caravan, the battlefield resembles a river crossing operation. Even today, this remains one of the most dangerous and difficult combat scenarios. To force the crossing, the attacking army must have exposed itself to missile fire from the opposite bank. Fording rivers is easier on horseback. Leading men on foot is also easier from horseback. To this writer, it appears that some nameless, ancient prince risked his elite troops and their horses trying to get across the Tollense River.

It is just one battle, perhaps, but it took place in a larger world, when the bronze economy was at its peak. After the Bronze Age ‘collapsed,’ iron came into greater use because it was easier to get than tin. More than a metal, the Iron Age was defined by a new economy of the professional warrior. We might even think of the ‘collapse’ as a kind of market correction.

I love this stuff. Fascinated by the bronze age collapse. So, some longhouses were a kind of barracks?