Why China Might Choose Another War Than Taiwan

A strategic scenario that gets less far-fetched all the time

“Over the past decade, the CCP has refined a highly nationalistic historical narrative that emphasizes past injustices inflicted by foreign powers on China,” Mark Metcalf writes in a 2020 article about the ‘Century of Humiliation’. Beginning with Chairman Mao’s first speech as master of China in 1949, it is a view of history in which China is the whole world’s victim.

The CCP “has used this interpretation to justify severe responses to foreign actions that it perceives as blatant violations of its sovereignty, threats to its territorial integrity, or insults to the Chinese people.” A series of military defeats, “unequal treaties,” domestic unrest, and civil war were followed by Japanese occupation. China is keeping a list of grudges. Some of them are more visible than others at any given time, but all of them hold value to the CCP as grudges.

During 2020, as the covid lockdowns began, analysts noted “a dramatic and aggressive turn” in Chinese policy. ‘Wolf warrior diplomats’ responded to ‘provocations’ while the Chinese economy suffered a series of ongoing breakdowns. Regime insecurity expressed as regime hostility. While the Taiwan Strait has been the most visible scene of nationalist saber-rattling during this time of crisis, China’s naval buildup may be insufficient to conquer Taiwan on its own.

If they want a softer target, Beijing has a weakening rival right on their doorstep, ripe for hybrid war conquest. Satisfaction of this very old grudge could even make Chinese ambitions against Taipei and their allies easier to achieve. A very rough sketch of this alternative scenario reveals that preparations have already been underway for years.

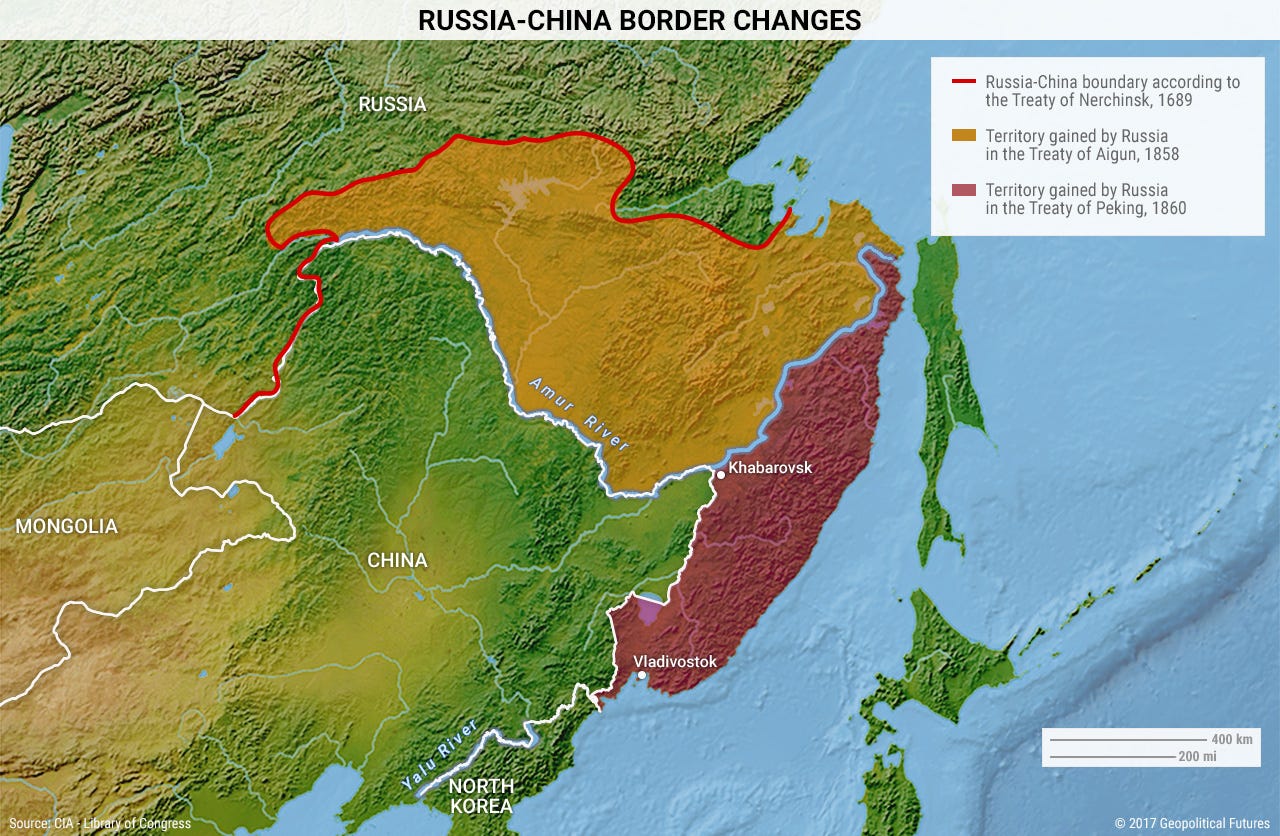

Russia’s eastward expansion into Siberia during the 17th century coincided with the rise of the Qing dynasty, which endured until the 20th century. Russian imperialism is therefore associated with the decline of the Qing. Signed in 1689 after decades of territorial conflict, the Treaty of Nerchinsk regularized diplomatic and trade relations, setting the boundary of the two empires north of the Amur River. It was the first time that China had ever signed a treaty with any European power.

The ‘Century of Humiliation’ began with Opium Wars. Qing defeats at the hands of the British, and then the Taiping Rebellion, left the dynasty too weak to resist Russian demands for territorial concessions. Signed in 1858, the Treaty of Aigun was soon followed by the Treaty of Beijing, which added more than two million square miles to the Russian empire without clearly demarcating the entire border, guaranteeing future armed clashes.

Russia intervened in the Boxer Rebellion by occupying Manchuria in 1900. This left Russia temporarily the most powerful foreign actor in China, effectively controlling the region and occupying Port Arthur in the Yellow Sea. The brief ascendancy ended with the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, a decisive Russian defeat on land and sea as well as the beginning of modern Japanese imperialism on the Asian mainland.

Soviet Russia returned in strength during 1929, winning a five-month conflict for control of the Chinese Eastern Railway. Stalin intervened again in 1934 to prevent the destruction of his client warlord in Xinjiang. Despite shared ideology, the relationship between communist China and Soviet Russia broke down during the 1960s, spurring Mao to develop atomic weapons and fight an unofficial, seven-month war with the USSR in 1969 over disputed areas in the middle of the Amur’s 1000-mile length.

Thus endeth our brief on the prehistory of the Chinese-Russian rivalry over the trans-Amur region. As Russia weakens today, potential strategies emerge for Chinese aggression in the Amur region aimed at extirpating the Century of Humiliation — as well as the humiliating internal collapse of China. Because of the nuclear dimension, all viable options will center so-called ‘hybrid war’ planning.

From the perspective of Chinese nationalism, “China won’t succeed in full restoration of borders without the territories that Moscow currently controls,” reads a 2024 report from the Robert Lansing Institute. “Russia does not match the concept of global China, as it can give Beijing nothing but resources, with most of them concentrated in the areas that historically belong to China.”

Chinese politics is an endless trick, Sun Tzu said. Chinese history textbooks emphasize that most of Siberia, with Western Siberia right up to the Tomsk region, is a Chinese territory, lost temporarily. And Chinese bookstores offer geographic maps where Russia’s territory (Primorye, Sakhalin Island, Eastern Siberia, etc.) is shown as allegedly belonging to China since the first Qin dynasty in the 3rd century BC.

Mao Zedong said ‘Russia seized too much land… More than 100 years ago, they cut off the lands to the east of Lake Baikal, including Boli (Khabarovsk), Haishenwai (Vladivostok), and the Kamchatka Peninsula. This account is still unpaid; we have yet to settle the bill.’

Chinese citizens make territorial claims to Vladivostok on Weibo all the time, and the CCP does nothing, effectively endorsing revanchist impulses towards the Russian Far East (RFE) on social media. Meanwhile, the ongoing crisis of post-Soviet population growth in Russia has given the more-populous China an opportunity to reverse the Russification of the trans-Amur region.

Chinese military men infiltrate as workforce and marry Russian women. China’s secret agencies take advantage of corruption in Russia and use illegal schemes to be legalized as citizens.

Beijing infiltrates local governments and plants ‘agents of influence’ there. The Kremlin has set up priority development areas, with Russian legislation limited, where China has lobbied for the benefit of their tenants.

Sinicization has aimed at taking control of the means of production of both guns and butter. By 2015, the CCP’s “farming rush” (zhongdi laojin), a global effort to purchase and exploit arable land, had produced a bourgeoning class of Chinese agricultural producers as well as regular flows of Chinese migrant workers in the RFE. Within the region, “Russia has a high concentration of defense industries in desperate need of outside investment,” political scientist Junhua Zhang wrote in a 2024 report.

While Chinese investment in the RFE has boosted Russian war efforts in Ukraine, it has also created a new Russian dependence on China for a vital portion of the state defense sector. Junhua notes two geographic points of dispute that have become points of seeming-cooperation between the putative allies.

One is the junction of the Amur (Heilongjiang) and Ussuri rivers, where Bolshoy Ussuriysky (Heixiazi) Island and the Russian city of Khabarovsk (with its population of 620,000) are located. The other is near the mouth of the Tumen River, not far from Russia’s great Pacific port of Vladivostok (population 600,000), where the Chinese border lies just 15 kilometers away from the Sea of Japan. In both of these strategic locations, Russia intends to harness China’s financial resources and manufacturing savvy to build two gigantic special economic zones.

It would be a mistake to see this as China merely helping Russia or cooperating towards mutual benefit. On the contrary, bridges into Russia are avenues of Chinese power into Russia. During 2023, the Chinese Ministry of Natural Resources ordered all new maps to feature Chinese names for eight cities in the RFE, including Vladivostok. On these maps, Heixiazi (lit. ‘Black Bear’) Island is shown as Chinese territory.

Making the Tumen River navigable to Chinese shipping traffic, thus giving Beijing access to the Sea of Japan, is not necessarily in Russia’s interest, either. Thus Putin hesitates to replace the low railroad bridge that blocks the channel, while China is already complaining about the new road bridge under construction to link Russia and North Korea, which will also block shipping on the Tumen. This is not peaceful cooperation. It is Chinese ambition and Russian avoidance.

One might dismiss all this and say that China agreed to a mutual border with Russia in 2008, but that presumes borders mean the same thing in Russia or China as they do in, say, Europe. Indeed, borderlessness is the very essence of Eurasianism, the underlying philosophy of the Russkiy Mir project. Russia’s borders are the limits of Russian bootsteps, in Vladimir Putin’s own formulation. Political boundaries are effete western conventions. The manifest destiny of Russia is limitless.

Although it differs in wanting to exploit the world-system rather than alter it, Chinese revisionism matches Russian revisionism on the ground. Beijing has seen the example set by Putin, and if the war in Ukraine leaves Russia weak enough, then the CCP might just imitate his ‘gray zone’ or ‘hybrid war’ model in the RFE. ‘Little green men’ can mysteriously appear, information spaces can be prepared for provocations that justify intervention, and sub rosa aggressions can test Russian resources. China has been watching the war in Ukraine with interest, to be sure, including its first eight years, 2014-2022.

Thus the report in June that officers of a special unit at the Russian FSB “fear that Chinese academics are laying the groundwork to make claims on Russian territory,” according to The New York Times, which has seen “an eight-page internal F.S.B. planning document” outlining their suspicions. In a turn that Putin will appreciate, “China is searching for traces of ‘ancient Chinese peoples’ in the Russian Far East, possibly to influence local opinion that is favorable to Chinese claims,” according to the FSB.

According to that document, Chinese espionage threats have created a “tense and dynamically developing” intelligence battle with Russia. “The Chinese plan to use the experience of Wagner fighters in their own armed forces and private military companies operating in the countries of Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America,” the FSB document says. Why not use PMCs in the RFE, then?

Indeed, Chinese spying has increased by orders of magnitude because of the war in Ukraine, which Beijing is watching very closely indeed.

China has long lagged behind Russia in its aviation expertise, and the document says that Beijing has made that a priority target. China is targeting military pilots and researchers in aerohydrodynamics, control systems and aeroelasticity. Also being sought out, according to the document, are Russian specialists who worked on the discontinued ekranoplan, a hovercraft-type warship first deployed by the Soviet Union.

“Priority recruitment is given to former employees of aircraft factories and research institutes, as well as current employees who are dissatisfied with the closure of the ekranoplan development program by the Russian Ministry of Defense or who are experiencing financial difficulties,” the report says.

What possible interest could China have in the ekranoplan, a seemingly dead-end technology that uses the ‘ground effect’ of air pressure to fly a few feet above the surface of the water? The obvious answer is perhaps the most likely: such craft would be most useful in shallow, constricted waters like the Taiwan Strait. Access to the Sea of Japan through the Tumen River would likewise advantage China against Japan in the event of war for the Taiwan Strait.

Put simply, Chinese war planners may see the RFE and the economic domination of Russia as their stepping-stone to other conquests, coming at the beginning of a future campaign of military absolution of shame rather than at the end. Furthermore, Putin seems to regard the risks of inviting this action as worthwhile. Like the gambing addict, he is only concerned with finding the next stake to continue his gambling. China is happy to keep lending him stakes.

Before the war in Ukraine, the Amur River was reputed to be the most densely fortified frontier on earth. Today, Russia would be hard-pressed to defend such a long frontage, presenting China with an opportunity to flip the Aigun treaty script. Generous leverage at the right time could induce a beleaguered Kremlin to give back some part of what was taken, back then, or allow China a greater stake and say in the Russian Far East.

Some part of this may involve fighting — cross-border drone attacks are one very likely harassing scenario — but China will want to keep the intensity level, and the stakes, low, for Russia has the world’s largest nuclear arsenal. China has modernized their nuclear deterrent, and continues to expand it, yet they have no plans to reach parity.

Instead, China lets Russia maintain their much larger nuclear force at much greater expense — while Russia also fights a simultaneous conventional war in Ukraine, again at tremendous expense, and Chinese leverage increases all the time.

In view of the world, China says there are “no limits” to their alliance with Russia and they do not want Ukraine to win the war. In practice, China limits their support for Russia and benefits from Ukraine prolonging the war. A collapse of the Russian system, or a face-losing result in Ukraine, might very well invite a turn in Chinese policy.

Many conditionals remain to be resolved. However, this scenario has become more likely than it was in 2022, and its likelihood increases every year that Putin’s war on Ukraine continues. I will keep an eye on this developing threat.

Russia's Economy Is Going Off The Rails

Russian business news website RBC is reporting that railroad employees in the heart of the country started taking two days’ unpaid leave per month in July because RZD, the state railroad company, is having trouble making payroll.

Okay, now I’ve read it - that’s plausible, and very bad news for the Siberian Tiger. You read “Tiger” by John Vaillant? Touches on a lot of the themes you’ve mentioned, funnily enough

First thought before reading - “anything’s better than 180km supply chain across missile/drone contested water”