Two Italian Saints Against A Sirocco Of Steel

The siege of Padua, 1509 - republished

Originally posted November 2022.

After defeat by a Holy Roman force at the Battle of Agnadello, the Venetians fled to their swamps, leaving the rest of the Serene Republic to be overrun. It seemed that the French King, Louis XII, had won the great Italian victory his Milanese allies wanted.

Venice was a potent sea power, but hardly a major land entity until 1405, when they captured the old Roman center of Padua in a siege. Ever-ambitious, the aggression of the lagoon-city against the Papal States after the death of Cesare Borgia in 1504 pushed Julius II, the “warrior pope,” to enter the League of Cambrai with France, Spain, and Vienna four years later.

It would not last very long.

For a moment, Emperor Maximilian seemed to have the Venetian hinterland, Domini de Terraferma, under his heel.

Yet this was the also the place where nationhood was being invented as a modern idea, so when the occupied mainland cities of Venice rose up in July, and the dashing Andrea Gritti retook the city of Padua on the Feast of St. Marina, Venetians celebrated it as a holy redemption of their state from a gang of mortal enemies.

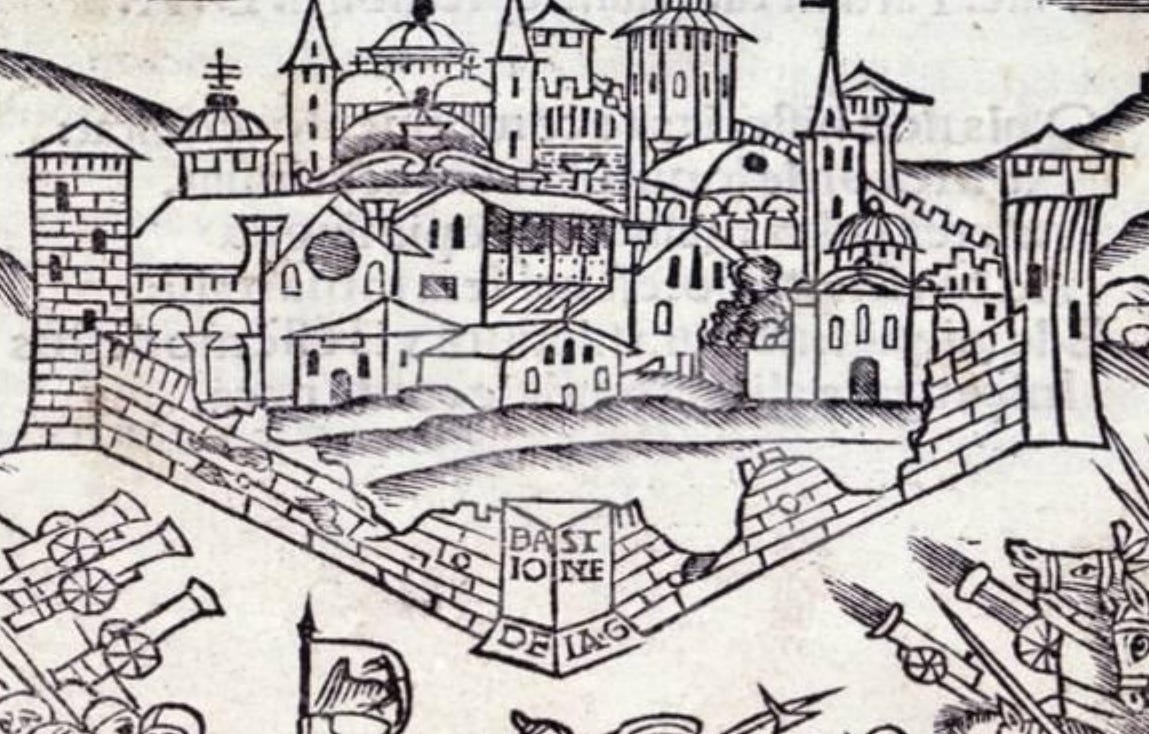

Likewise, the ensuing siege of Padua was to be celebrated as a miracle. Thus the artwork above which, as representations of sieges in previous eras, is not meant to be a realistic portrait of the actual siege. It is an idealized tableau of fifteen grueling days rather than an accurate history of a particular assault.

Its accuracies are thematic. Padua, the city of Dante Alighieri, is defended by the heavenly intercession of Mark the Evangelist (patron saint of Venice, left) and Anthony of Padua (patron saint of Padua, right). But the real-world story is also included in the visual telling.

Unseen here are the cannons defending Padua. More than 120 studded the improved city defenses before the allied army arrived. Dominican Giovanni of Verona, known as Brother Giocondo, led the citizens in a frenzy of construction to improve the walls and bastions, dredge and fill the moat, store up supplies. There was time for theatrics: Doge Loredano told the Venetian senate he was sending his own sons to Padua, so the nobility sent their sons, too.

In the illustration, we only see the batteries of siege guns brought over the Alps — which, just in the telling, describes the medieval logistical nightmare involved. By this time, stone shot was being replaced by iron, while the guns themselves weighed less than two tons.

According to Christopher Duffy’s Siege Warfare: The Fortress in the Early Modern World, 1494-1660, considered the standard reference history of the development of the gunpowder fortress, this was a potent siege gun. For a smaller, iron ball, shot from the largest cannon that could be hauled over mountains, was the best combination for bombarding upright medieval walls into piles of small fragments that storming parties could climb with ease.

In addition to the terrain and limited road infrastructure, the polyglot Holy Roman army was already showing a slouched character that would come to be known as schlamperei under the Austro-Hungarian Hapsburgs in the 19th Century. Half of them were mercenaries. Diversity was a necessity, but it was always to be the enemy of efficiency.

Venetian chronicler Marin Samudo wrote that the host, which he numbered at fifty or sixty thousand, included German and Swiss mercenaries, papal troops, contingents from Ferrara and Mantua, as well as Louis’s 500 elite mounted men-at-arms. “It is certain that if there were a little rain, half of them would disappear,” he complained as the force camped outside the walls of Padua.

Samuda called on the infamous Mediterranean storms blowing off the Sahara to intervene: “I wish there could be a little sirocco for six days.”

The French king’s father, Charles VIII, had invaded Italy in 1494 with seventy cannons brought to Italy by galleys, the greatest gunpoweder siege train that Europe had ever witnessed. Not to be outdone, Louis XII wanted an even larger train, and insisted Maximilian I should come take personal charge of it at Padua. His ally promised to do so, but dallied too long.

By the first week of August, Louis was ready to quit Milan and go home with a public flounce. “And where is the emperor? I know where he ought to be,” he said. “I have made my mind up to leave here on Monday” 6 August, before the siege batteries had even been finished. He would miss seeing Maximilian lead the final abortive storming attempt in person.

Louis had loved war as a young man and yearned to prove himself in what would come to be known as the Italian Wars. Siege was not much fun, though. Sickness and desertion decimated the ranks. Conditions were poor in the field, and the Venetian garrison at Trevisa 25 miles from Padua sent harassing patrols every other day in search of soft targets, such as unguarded wagons. Such miseries made for inglorious campaigning.

Altogether, the primary sources say that Duke Alfonso I d'Este, the greatest enemy of Venice, set 200 guns before the city. Many of these would have been needed to defend the fortified camps of the besieging army from sorties and raids by light cavalry, however. For as huge as that army was, it still never got large enough to fully encircle the city.

Nevertheless, work proceeded until 14 September when the heavy battering guns were in place. (This grouping of two or more cannons to punch a hole in fortifications is where we get the term “battery” in application to artillery.) After the usual last invitation to surrender, the battering began.

It was no small thing for a garrison to refuse quarter in these circumstances. The true power of Charles VIII’s legendary siege guns had been his policy of massacring garrisons once a breach had successfully been stormed. After the first examples were made, cities opened their gates to him with alacrity.

Once the Holy Romans tried storming the breaches made by d'Este’s guns, however, they discovered the reason for this stoic refusal. In their hour of need, the Paduans had figured out “this one neat trick” for defeating a breach in your walls.

As described by Niccolo Machiavelli in Book 7 of his 1520 Arte Della Guerra, the Paduans had erected a “retirara,” an earthen rampart protected by a ditch, inside the perforated bastion walls. Defended with every available missile weapon, including the primitive gunpowder small arms of the era, they had turned the breaches into a killing zone with this new layer of defense.

The first assault by Spanish infantry on 20 September was a moral and material disaster. Further attempts failed again on 26 and 29 September. During this last embarrassment, the elite French cavalry declined to take their turn at the breaches. A frustrated Maximilian broke camp and withdrew during the night of 30 September, so the defenders saw no one as October dawned on the empty, ruined environs of Padua.

Ferrarese chronicler Antonio Frizzi notes the breach was substantial, and blames the supposed treachery of German generals for the failed assaults. It seems more likely that as mercenaries, the German men esteemed their lives rather than imperial honor.

Upon raising the siege, Maximillian’s first act was to dismiss every hired soldier. Louis had already done that, writing to the new king of England, Henry the VIII, on 13 September that “the King of France has disbanded his army, with the exception of those men-at-arms who form his standing army.” It was a sniffing dismissal of how his own mercenaries had performed under fire.

A military revolution was underway. It was to produce the first standing professional forces that would come to define the modern era — the definitive beginning of military history as opposed to the larger history of warfare.

According to Paduan tradition, theirs is the oldest city in northern Italy, founded in 1183 BC by a Trojan prince, according to Virgil. Home today to the fifth-oldest surviving university in the world, it is certainly quite old, and its blessed delivery from foreign invaders validated the republican statehood of Venice.

Having seen what cannons could do, the Serene Republic considered them a strategic priority, setting up what Duffy considers the earliest example of an artillery school in 1526. Venetian gun tubes were plain, not ornamental at all, and easily switched from land carriage to wall mount to galley prow.

Once the League of Cambrai had disintegrated, and all of Louis’s former allies had turned on him, Venice could resume its maritime superpower status and minor land power status. Another lesson learned in the War of the League was that because gunpowder sieges are incredibly expensive, foreign invaders could be deterred by making cities even more expensive to crack.

As Christopher Duffy explains, it was from this moment that Italian engineers began to design a new kind of fortification to resist artillery fire and maximize the effect of defensive artillery. Known as the trace Italienne, examples of the style abound worldwide thanks to the globalization made possible by ships and guns and gunpowder empires. Padua, 1509, is the origin story.

In my worn copy of Vezio Meligari’s Great Military Sieges, this illustration includes an inscription in antique Italian referring to the walls of Padua as “the obsidian.” I have yet to confirm whether this name refers to the color of the stone used to construct them. Obsolete as they were, they had proven to be enough, even against cannons.

While no defenses can stand forever against determined attack by an enemy with infinite means, siegecraft has always been a business of managed risks. Henceforth, the squabbling city-states of northern Italy would seek to make their own conquest too expensive for the squabbling emperors of Europe, and their scheming popes, to risk.

Critics of Duffy’s thesis point out that on many occasions, well into the 17th Century, medieval walls could suffice in a pinch as long as an aroused citizenry had time to throw up a retirara. There was no economic cost-benefit analysis by which most cities could afford to convert their walls in peacetime.

All true. More to the point, though, is how civic spirit infused such events — the breach and the hasty defense inside of an obsolete wall — as they recurred in the brutal sieges of 16th and 17th Century wars, and in their portrayals as art, and in public memory.

Seen as a risk management decision, it is clear that this technological transition incentivized modern state formation processes. Poliorcetic revolutions — rapid changes in the way people create and conduct sieges — do this every time, and it is visible in the art, for a work of siege art must always contain multitudes.