The Secret Lives Of Secret Workers

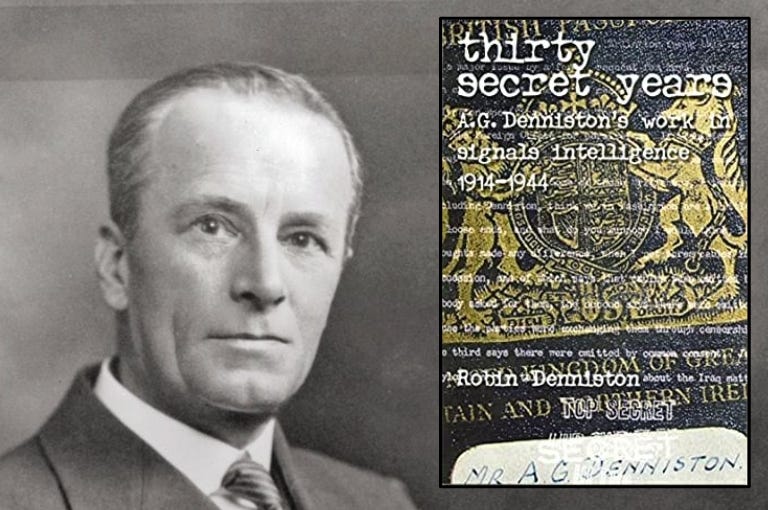

A.G. Denniston and Room 40

Originally published in November 2021. My free subscriber base has grown twenty times over since then. Please consider supporting my work with a premium subscription.

Alexander Guthrie Denniston was an expert in German literature teaching at the British Navy’s Osborne prep school when the First World War broke out. Offering his services to the Admiralty,…