The Fine Art Of Assaulting Mud Brick Fortifications In The Middle Kingdom

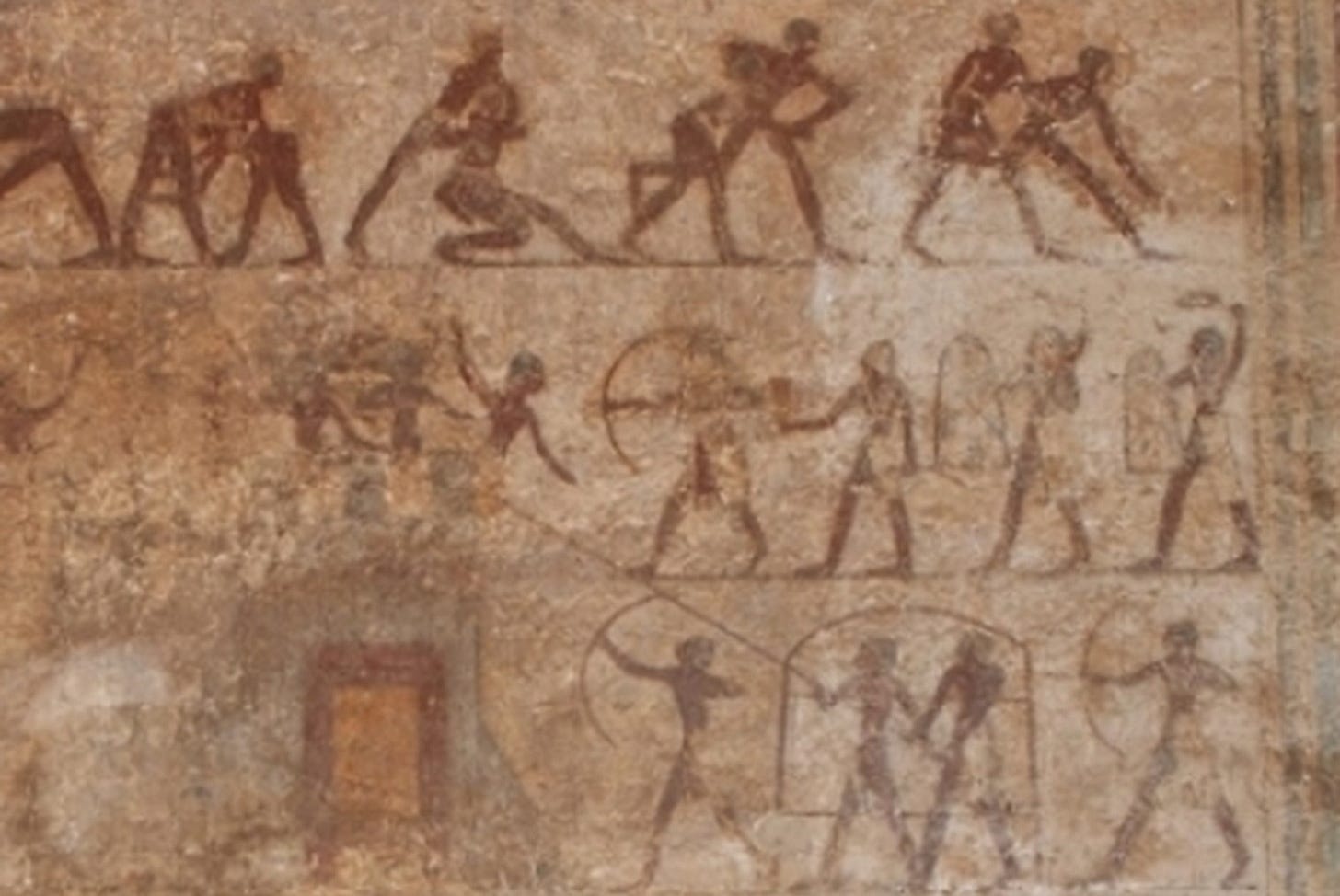

A regular series on poliorcetic portrayals

Symbolism, as well as the archaeology of defensive walls, point to an epoch of cities at war, and wars over control of cities, from before the First Dynasty. Before the Old Kingdom coalesced, th…