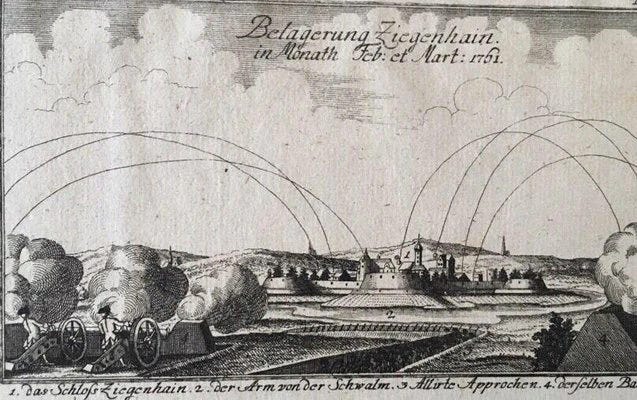

The Art of Indirect Fire in the Seven Years' War

A poliorcetic engraving

Reposted from June 2022, when I had 83 subscribers.

There is not much information on Simeon Ben Jochai, the Jewish engraver who etched the above image into colored copper. Few artistic professions were open to Jews in most of Germany at the time; printing, lithography, and engraving were exceptions. Like the Jewish cartographers who revolutionized mapmak…