Modernity: A Motte-and-Bailey Argument

On the taming of the European aristocrat

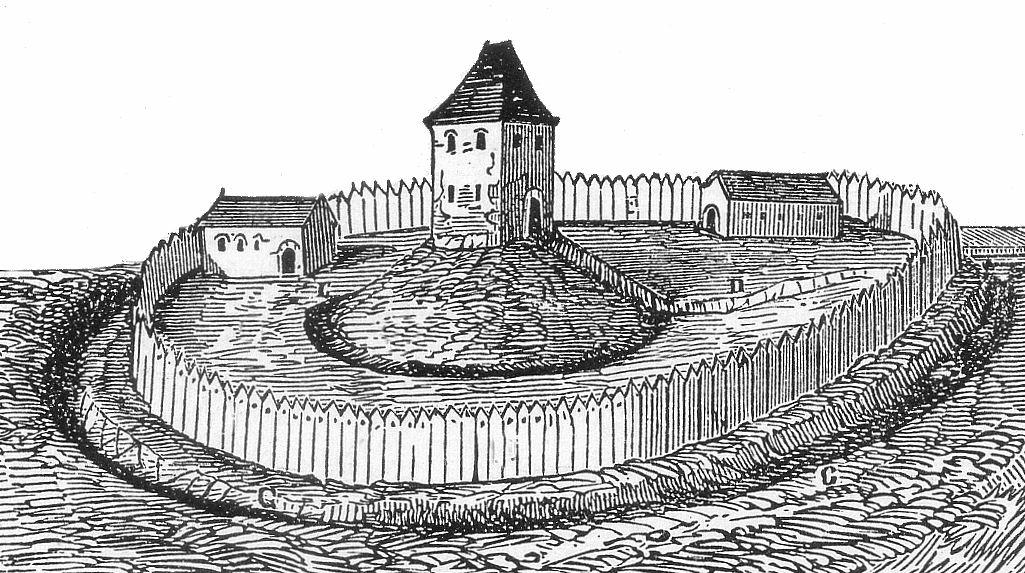

In argumentation, the ‘motte-and-bailey’ fallacy is a conflation of two positions that seem similar, the motte being easily defended while the bailey is more difficult to defend. This metaphor derives from a practical reading of motte-and-bailey structures. All fortification is about managed risks. As Carl von Clausewitz said, “time which is allowed to pass unused accumulates to the credit of the defender.” An attacking army that crosses the ditch, or moat (‘motte’ is where we get this word), and then gets over the palisade or wall, will enjoy severe advantages over the defender of a small bailey. Nevertheless, standing on a ‘cone’ of earth, even a small tower or keep will still resist attack by men on foot for some time, making it possible for friendly forces to relieve the defenders, or for negotiations to limit the carnage. The palisade is easy to defend, while the bailey is harder to defend, yet the arrangement creates opportunity to manage risk upon enemy breakthrough. An alarm raised fast enough — say, a dog let free in the yard barking at the intruders — can save the occupants of the bailey from a nighttime storming party, for example, even if the property is left damaged.

The motte and bailey design imposes risks on the attacker at relatively low cost to the occupant. A motte-and-bailey castle is cheap. It can be made with local labor and materials. Plans can take advantage of local geography, such as hilltops and bodies of water, to maximize the risks an attacker would take to invest it. The English language uses this term ‘investment’ to describe the material resource demands of siegecraft: evidence of the risks that even simple, cheap fortifications could create for anyone who wanted to harm the prepared homeowner. These earliest castles were indeed almost all private homes. In his 1992 book The Medieval Siege, historian Jim Bradbury writes that “that the emergence of 'castles' was in most cases simply the improvement of the defences of existing defended residences.” Examples from Medieval Europe are not far advanced from prehistoric ditch-and-palisade structures. “Purpose built castles would emerge, but many of our best known early castles were existing residences, usually already defended,” he writes. European geography lending itself to positional defense, “there was a considerable amount of such improvements made in the tenth century, which has therefore been seen as the time when castles first appeared, but it becomes a less dramatic development when viewed in this way.”

A man’s home is his castle, Sir Edward Coke declared in 1644. That same year, parliamentary troops were repulsed in another bloody attempt on the fortified manor known as Basing House, home to the Marquess of Winchester. Standing on a natural site to command a major crossroad, the manor grounds appear to have been inhabited since the Stone Age and were first fortified during the 13th century with a motte-and-bailey castle. Dirt ramparts and a broad ditch reinforced the obsolete brick walls in the 17th century, making Basing House a small, yet formidable artillery fortress during the English Civil War. When a real army did show up with a real siege train, however, Basing House was doomed. Any small castle was doomed. No man’s castle could withstand a determined attacker forever, especially if they had powerful guns. During the 17th century, European aristocrats altogether stopped building personal castles for defense, as there was no point anymore, and competed instead at building castles for show — palaces. The age of Versailles loomed. Crenellations and battlements became aesthetic elements while the machicolations for arrowfire disappeared, as there were no ememies under these towers and walls. The private defensive castle vanished, the centralized state rose, and the decline of European aristocracy began. Cannons had resolved the motte-and-bailey arguments of provincialism. The metropole had conquered.