The Bronze Lie: Shattering the Myth of Spartan Warrior Supremacy. Osprey Publishing, 2021. 615 pages.

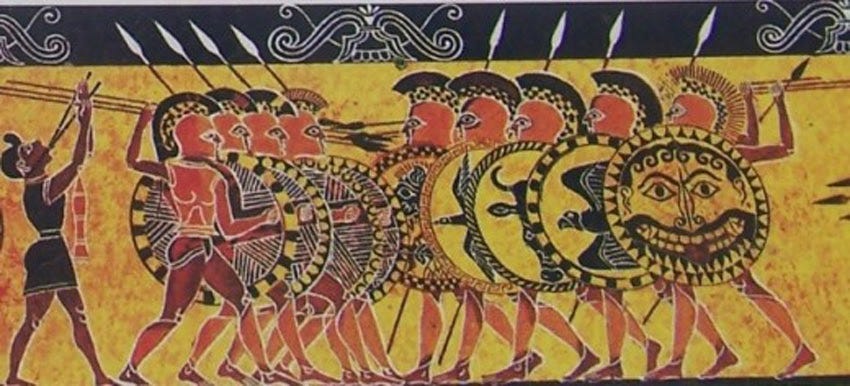

Above: the Chigi vase, which depicts Spartans that look very unlike our modern filmic ones.

“One on one,” author Myke Cole tells us of the Spartans, “they weren’t particularly tough, but…their ability to fight together as a disciplined unit far exceeded t…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Polemology Positions to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.