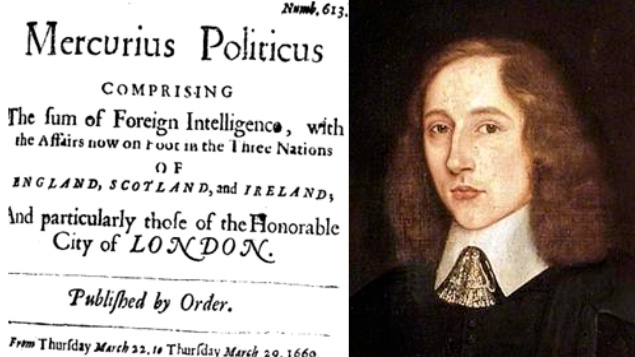

Mercurius Politicus is considered an early newspaper, but today we might see the format as a newsletter, for each edition was printed with articles in sequence, as a single column. John Fowke, merchant adventurer of London, purchased an advertisement in the 22-29 March 1660 edition of the paper to refute widespread misinformation about his role in the t…

Substack is the home for great culture