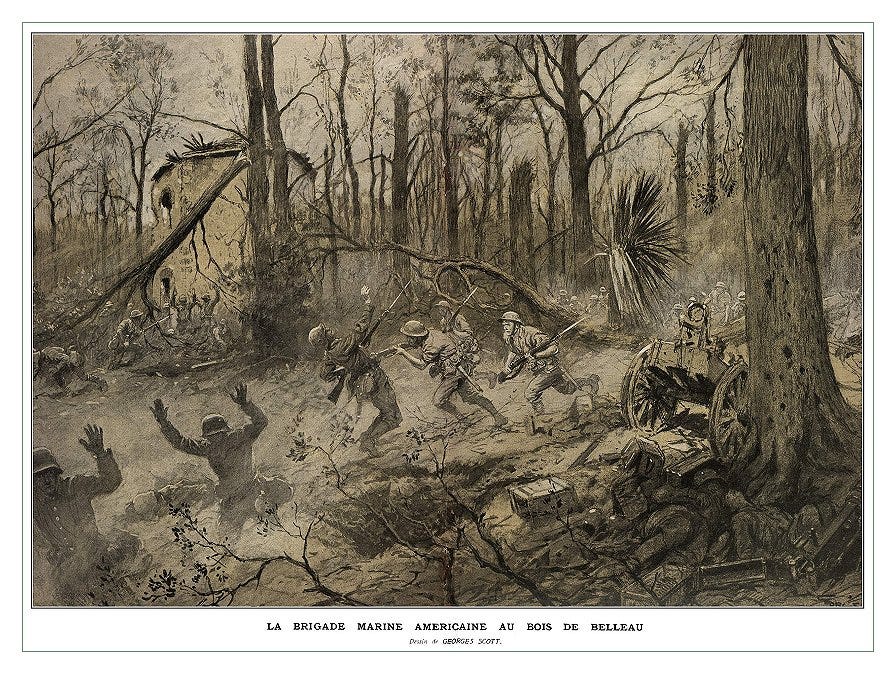

Hero of 1918 'Did Not Even Know What The Marine Corps Was' When He Joined It

A memoir of the Great War

“The only map our battalion had was a little hashered map about six inches square and very inaccurate,” Lt. Col. James McBrayer Sellers, USMC, wrote of the battle at Belleau Wood. Even this was unavailable to him. “Our company commander did not even have a map.” Like much else the Americans had to work with, the quality of the cartography that France su…