Hazardous Histories: Twelve Battleships Destroyed By Internal Explosions

On ammunition safety and Murphy's Law (REPOST)

Originally published in October 2023. My free subscriber base has doubled since then.

A battleship is a great, big bomb waiting to explode. The naval architect must perform a balancing act between armor, machinery, and those huge, heavy guns. No perfect protection scheme was ever devised for the magazines of battleships. Famous examples of battleships exploding and sinking (or exploding while sinking) in combat abound: the IJN Yamato, the HMS Hood, and the HIRMS Borodino all experienced catastrophic magazine fires. But it is also striking how many times these ships exploded as a result of accidental or incidental ammunition fires, also usually with catastrophic loss of life. One day I intend to publish a video on this topic, which has a morbid fascination for me. We are compelled by the sight of big things failing. Battleships were the most complex technological constructs ever devised. As we have recently witnessed with the Israeli defenses around Gaza, catastrophic cascades of technological failure can happen to military schemes which lack redundancy. Even the best technology can fail, including the most highly-developed safety systems, which in turn usually exist to prevent past catastrophic failures from recurring.

Safety engineering did end the era of self-destructing battleships. These accidents all occurred in ships that were constructed during a distinct period of battleship development that ended after the First World War. New ammunition loading systems, safety mechanisms to prevent flashover between compartments, and fire suppression equipment were coming into use. As we shall see, temperature regulation and ventilation were also key concerns. However, the biggest safety risks lay in old, corroded, or badly-stored ammunition. The deadly turret explosion on board the USS Iowa in 1989 was a result of a safety system failing — the center gun was overcharged with bags of old, unamended gunpowder, one of them being turned sideways — and also an example of redundant safety systems preventing a more complete, far deadlier disaster, as some sailors in the turret actually survived. More than 2,000 sailors were on board at the time, so the fact that only 47 of them were killed is a credit to the engineers who built the Iowa, even if the resulting fiasco of an investigation was a discredit to the US Navy itself.

Indeed, one of the commonalities of these incidents is how often navies ignore obvious, if inconvenient, explanations for these accidents, projecting malign intentions onto enemies, real or imagined, imposing conspiratorial causes onto what are most likely accidents. Battleships were inherently political technologies. More than merely showing the flag, they were national endeavors. It was the most expensive arms race the world had ever seen. Politicians balked at the price per ton and limited displacements, forcing the designers to be creative, sometimes with disastrous results. Nevertheless, these vessels carried the pride and prestige of the peoples who paid for them, so we should not be surprised that various publics and politicians have instinctively preferred to blame enemy action for these disasters rather than accept their sudden loss has been an embarrassing mistake. Individual people do not even need yellow journalists to help them rationalize away the unthinkable reality. We do it quite naturally.

1 - USS Maine 1898

The explosion of the USS Maine in Havana harbor on the evening of 15 February killed 266 of the 350 sailors on board. Maine had been chosen, indeed kept in readiness for months, because she was the most powerful American warship in the Atlantic that could operate in the confined space of the harbor. Because the explosion was centered in the bow, Cap. Charles Dwight Sigsbee, whose cabin was in its traditional place at the stern, was one of the 84 survivors. While the explosion did not lead directly or immediately to the ensuing war, it “has fueled two main conspiracy theories: first, that the explosion was caused by a bomb or mine planted by the Spanish; and second, that the United States sunk the ship deliberately as a ‘false flag’ operation in order to inaugurate a policy of imperial expansion in the Caribbean,” Christopher R. Fee and Jeffrey B. Webb observe in Conspiracies and Conspiracy Theories in American History.

The first official report in March 1898 did not help matters. The board of inquiry blamed a Spanish mine, though it did not explain how the supposed device happened to float into the Maine. A Spanish government report noted the absence of dead fish in the water around the ship and suggested that an underwater explosion was not to blame. A second US investigation in 1911 also concluded that a mine was involved, but located its impact point in a different place on the hull. Nevertheless, the truth was slowly emerging. “From the appearance of the wreck, the board correctly placed the center of the explosion in the 6-inch reserve magazine, located between frames 24 and 30 on the port side inboard of a coal bunker,” I.S. Hansen and D.M. Wegner explain in “Centenary of the Destruction of USS Maine: A Technical and Historical Review.” Published in the Naval engineers journal during 1998, the article is a response to a recent National Geographic article which had suggested the mine explanation was still viable.

By 1976, when Adm. Hyman G. Rickover wrote How the Battleship Maine Was Destroyed, it was quite apparent to safety engineers that the most likely cause was an internal fire. Bituminous (brown) coal, kept in bunkers alongside the ammunition compartments as ‘extra protection’ against penetrating shells, tended to form volatile dust. Combustion from inadequate ventilation of brown coal “occurred more than once every year on Navy ships at the time,” according to Hansen and Wegner. “The bulkhead between the bunker and the magazine was a single 1/4”-inch plate without insulation, and some of the copper powder tanks were improperly stowed in contact with it.” On the other side of that thin wall were “five tons of brown powder explosive ammunition” for the six-inch guns. “With long term heat transmission, black powder can be ignited at temperatures as low as 650 degrees F,” therefore “it would not have taken much of a smoldering coal fire to transmit this temperature through the thin bulkhead to a powder tank in contact with it. Combustion of coal begins at about 800 degrees F, and a glowing fire would have an even higher temperature.”

She was “the first American steel warship to be fully designed in-house by the Navy and completely built with American made materials,” so her loss was a huge blow to American prestige. Yet it was her very newness and smallness that led to her loss. Originally conceived as a ‘second rate battleship,’ the Maine took almost a decade to build, going through redesign after her keel was laid, to sail as an ‘armored cruiser.’ Inexperienced naval architects had simply tried to do too much with too little displacement.

2 - IJN Mikasa 1905

Japan felt itself to be the equal of the British island nation and empire, so it is unsurprising that the Imperial Navy turned to the Royal Navy as their modernization guide. “The pre-dreadnought battleship Mikasa was launched at Barrow in 1900, when Japanese naval officials and sailors would have been a relatively common sight in the town,” Ruth Mansergh writes in Barrow-In-Furness in the Great War. Delivered to Japan by the end of 1903, her Victorian livery was replaced with a coat of haze gray, and so she became the IJN flagship as the Russo-Japanese war got underway. Adm. Tōgō Heihachirō observed the Battle of Tsushima on board the Mikasa, effectively ending the war. The Second Russian Pacific Squadron scored at least thirty direct hits on the Mikasa, but their ammunition was not as explosive as the Japanese warheads, being made of guncotton instead of picric acid compounds, so none of the hits put the ship out of action or started significant fires.

Six days after the peace treaty was signed, however, the Mikasa exploded in the harbor at Sasebo Naval Arsenal, where she was tied up at the mooring, waiting for a refit and a fresh coat of paint. Most of the 350 sailors who died were fighting the fire when it reached the ammunition compartment. The resulting explosion threw men on the deck hundreds of meters through the air. She sank, killing everyone trapped below. Accusations of treachery soon followed but no evidence emerged. Raised and repaired a year later, she sailed again in 1908, becoming a coastal defense ship in 1921. The hapless Mikasa then ran aground, receiving severe hull damage. It would be two years before she was moved again, this time to become a museum ship in honor of Adm. Tōgō. “At the end of the war, the American forces dismantled the ship’s armaments and it was not until 1955 that a drive to restore the ship to her former glory was initiated by the Japan Times, which ran a fundraising campaign,” Mansergh writes. “The refurbishment was completed in 1961 and since then she has been a museum ship in Yokosuka, Japan.” Mikasa is the only remaining example of a pre-dreadnought battleship anywhere in the world. I hope to visit her someday.

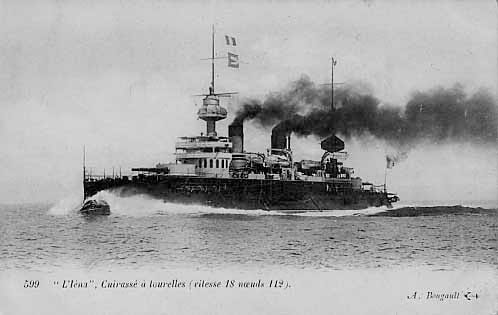

3 - MN Iéna 1907

The Marine Nationale did not obtain ship ‘classes’ in this era so much as they ended up with families of ships. As I have explained before, French naval engineers in this period conceived of themselves as artists in a school, all riffing on similar themes to create unique works of art. The Charlemagnes all had face-hardened Harvey steel armor but none of them had exactly the same layout or weapons as the others. Known as la flotte d’echantillons (lit. ‘the fleet of samples’), the French pre-dreadnought fleet was a colossal procurement failure. It also produced some of the most aesthetically-hated battleships of all time; fans of the battleship relish the steampunk ugliness of them.

The Iéna had been in drydock for eight days when, on 12 March 1907, starting at 1:35 PM, a fire caused a series of explosions over an hour and ten minues. The magazines had not been unloaded before docking and the water had been drained from the drydock, making it impossible to flood the ammunition compartments. Courageous efforts to get the lock open took too long. The 100mm magazine finally detonated, turning the ship into scrap. (She did, however, technically sink in the now-flooded drydock and therefore makes this list.) A total of 118 crewmen and dockyard workers were killed by the explosions along with 2 civilians in the suburb of Pont-Las killed by flying fragments of the ship. According to a digest article preserved in The American Periodicals Series for 1911, immediate explanations involved “an anarchist plot or to sedition among the crew. There was no evidence of either.”

Investigators focused on three theories, “wireless waves upsetting the unstable ehcmical or electrical equilibrium which exists in the components of modern powders; an accident, due to carelessness in the handling of powder or projectiles; and absolutely spontaneous detonation” of the ‘Poudre B’ explosive.

Colonel Marsat, indeed, showed that it was ‘mathematically impossible’ for this powder to explode of its own accord. But M. Vielle, the distinguished chemist, and General Gossot, a great artillerist, admitted that such an explosion was possible. Captain Lepidi went further and declared that not only was this powder dangerous, but the peril from it was extreme. ‘ I do not assert,’ he said, ‘that all our ships will blow up to-morrow, but I do say that all of them might blow up.’ A few weeks later his statement was signally justified. A quantity of ‘B powder’ took fire spontaneously while the committee were examining it, and, had the quantity been large, there would have been no committee left.

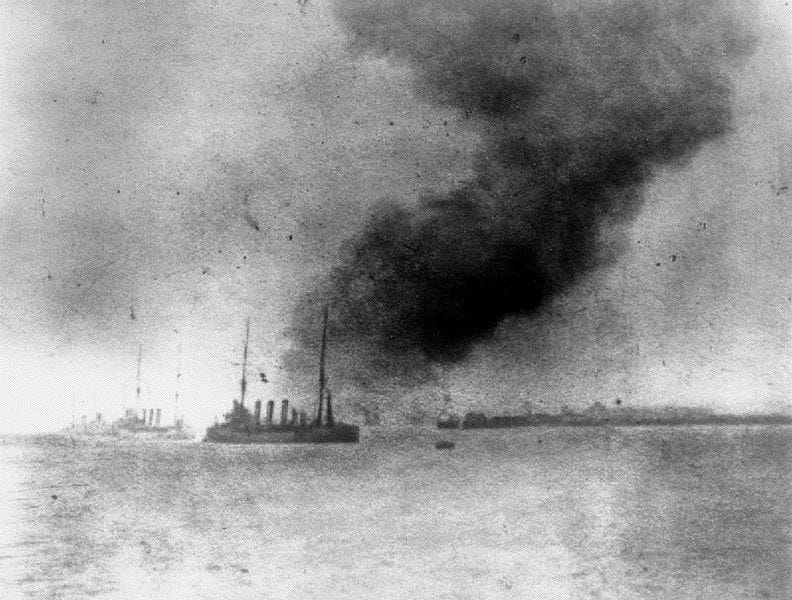

4 - MN Liberté 1911

“After the Iéna catastrophe there was much inspection of explosives in all navies,” the American Periodicals Series article continues. “The stocks of cordite were overhauled and chemically tested. So unsatisfactory were the results of the tests in many cases that tons of this propellant were burned or emptied into the sea.” Just weeks after another disaster, the uncredited author writes, it is “the expert opinion of Europe” that “the catastrophe involving the giant French battleship Liberté — blown up in Toulon harbor with a loss of four hundred lives a few weeks since — comes as the climax in a series of kindred disasters attributable to the instability of modern explosives.” Repeated experience was slowly overcoming reflexive suspicion.

Recalling the Maine, as well as other recent accidental magazine explosions on cruisers and battleships, the article notes that “refrigerating machinery was fitted to the magazines of warships to keep the powder cool” after navies realized that prolonged heat destabilized their ammunition, essentially slow-cooking it. However, environmental engineering was in its infancy. “This refrigerating machinery has not been perfected, however, and to this circumstance the naval experts attribute the disaster that befell the Liberté.” Having constructed waterline models of several pre-dreadnoughts, including the Mikasa above, as well as a cousin of the Liberté, I can certify there are for too many of those deck air scoops you see old-timey cartoon characters jumping into and shouting down. Those aren’t speaking tubes, they are primitive air conditioning. Also a conspiracy against future model-building enthusiasts. Ahem.

Liberté and her sisters and cousins were painted in a distinctive horizon blue color with linoleum decking instead of wood. Essentially a more powerful pre-dreadnought, she was already obsolete when she sailed in 1907, for the eponymous HMS Dreadnought had hit the waves. She and her extended family constitute the bulk of the intermediate battleship type known as ‘semi-dreadnoughts.’ Never successful, at least they were not eyesores. Unrecoverable, and conveniently in shallow water, she was scrapped at the site of her sinking. Chemistry turned out to be the problem and the solution. Ammunition manufacturing quality controls were improved and the Marine Nationale had no more catastrophic explosions.

5 - HMS Bulwark 1914

British naval architecture and manpower planning followed a very different track from French design in the late 19th century. Unlike the testy Third Republic, which could not bring itself to reduce shipyards or cashier superfluous admirals, London was ruthless about rationalizing their defense industrial base and eager to put crusty salts on half-pay reserve status. The Bulwark was the oldest of the ships so far listed when she exploded and sank, and she came from the largest and most consistent class. Her crew could have been swapped with any other London-class vessel and the sailors on both ships would have instantly known where everything was and how to sail her. She was close enough to predecessor Formidable class vessels, the preceeding Canopus-class ships, and their immediate ancestors that sailors could upgrade without so much instruction. Efficiency meant the admiralty could produce more ships faster than France, while their ships could sail and fight as squadrons better.

When she was commissioned in 1899, the ancient cross-channel rivals were still enemies. “HMS Bulwark was one of five pre-Dreadnought battleships laid down in response to France’s turn of the century shipbuilding program,” Lincoln Paine writes in Ships of the World: An Historical Encyclopedia. “One of the first major units fitted with a Marconi wireless telegraph, Bulwark served as a flagship of the Mediterranean fleet, based at Malta, from 1902 to 1907.” Obsolete now that the Dreadnought was at sea, the ship bore a proud name. “Detailed to the Home Fleet, formed as a counterbalance to Germany’s North Sea Fleet, Bulwark served as a divisional flagship until 1911 when she was trasferred to the Fifth Battle Squadron of the reserve fleet.” Changes of command led to changes of habit. In some squadrons, the ethics of manly disregard for safety meant that ammunition compartment doors might be propped open, and charges stacked in the corridors, to speed up gunnery practice and impress the admirals. Whereas these ships had been designed with magazine safety in mind, humans are adept at overcoming the most advanced safeguards through intentional disregard.

“On November 26, 1914, Bulwark was anchored off Sheerness when at 0753 the ship was ‘rent asunder’ by a massive internal explosion caused by the poor storage of cordite charges, some of which were twelve years old,” Paine writes. It was the largest accidental explosion in the history of the British Isles. “The ship sank instantly, taking with her a full compliment of 781 ranks and ratings.” Fourteen survivors were plucked from the water; eight died of their injuries. One officer’s jacket was recovered from the wireless antenna of the Bulwark‘s sister ship Formidable lying at anchor some 2,000 feet away. As the accident occurred in wartime, everyone at the scene reverted to intentional causes. Panicked witnesses reported the mast of the Bulwark, now sticking out of the water, as a German u-boat periscope. The real causes were soon discerned, amd even confirmed by the inquiry, but similar problems led to Royal Navy losses at the Battle of Jutland in 1916. Less than half a year after the Bulwark exploded, a mine layer, the Princess Irene, broke her record by exploding in the same harbor. Parts of that vessel rained down as far as ten miles away. Unsafe ammunition handling by inexperienced crewmen once again took the blame when the review board was finished.

6 - RM Benedetto Brin 1915

As though a global pandemic was spreading, now it was the turn of the Italian Regio Marina. The Benedetto Brin, a pre-dreadnought battleship named for the naval engineer who built a modern Italian Navy in the late 19th Century, erupted in a ball of flame just after 8 AM on 28 September 1915 while anchored at Brindisi. A fire in the ammunition compartment below the rear main turret set off a massive blast. The rear turret was thrown into the air by the explosion, which ripped through the back half of the ship in a sickening shudder of steel and heat, exposing half of the gun tower before the entire gun-stack fell over into the sea. This spectacular sight was the salvation of ships moored close to her, as it directed the force of the blast upwards rather than outwards. A mushroom cloud rose over the harbor. The hull was split open. By the time her sister ship Regina Margherita and the rest of the anchored flotilla had even begun to respond, the ship’s keel had already settled on the soft, muddy bottom of the channel, and more than half the Benedetto Brin‘s crew were dead. Many sailors survived the immediate effects only to succumb to injuries from blast, heat, and shock later. Altogether, 454 of the 841 Italian sailors aboard were killed.

Austrian and German u-boats were operating in the Adriatic. However, no submarine had penetrated the channel, for the barrier net at the harbor mouth remained unbroken. Nevertheless, before the smoke had cleared, Austro-Hungarian action was blamed all around. The official report on the annihilation of the Benedetto Brin made no determinations at all, instead posing a number of alternate theories: sabotage by a ‘false priest’ using the Catholic church as diplomatic cover to commit an act of sabotage; a double agent in the Italian Navy; or an accidental ignition of ammunition, a cause which everyone dismissed. Unsurprisingly, no evidence that the Central Powers were responsible for sinkingthe Benedetto Brin ever emerged. Yet even a century later, enemy espionage is by far the most commonly-cited explanation for what was almost certainly an accident.

The reason is Ferdinando Martini, a minor Italian minister and navalist, told a story of espionage and intrigue in Zurich, Switzerland in his published ‘diary’. This sole source remains widely believed in Italy and even among academics. To Crown the Waves: The Great Navies of the First World War, a publication of the Naval Institute Press in Annapolis(!), has endorsed this conspiracy theory in the online libraries of American universities. At his oddest narrative moment, however, Martini reimagines another, later accidental deadly explosion — that of an ammunition barge while it was tied up alongside the armored cruiser Etruria at the harbor of Leghorn in 1918 — as a ‘false flag’ operation to fool suspicious Austrian spies into accepting information from Italian double agents again. It is exactly the sort of nonsensical fantasy story people make up after long, dismal, and disappointing wars, which does describe the First World War for Italy.

7 - RM Leonardo da Vinci 1916

France was already producing a dreadnought class, the Courbet class, to replace the Liberté family of ships that sailed before the war began. (As it happens, I am working on model of one right now.) To counter Paris, the Regio Marina got to work on the Conte di Cavour class ships, building three of them. Superfiring (stacked) turrets fore and aft, with a central turret, allowed all thirteen of her main guns to fire on either broadside. She was built to be formidable in the stern chase as well, but came out of the yard a bit slower than expected. Just two years past commission when the war began, Leonardo da Vinci saw no action before she suddenly exploded in Taranto harbor on a calm August night, killing 21 officers and 227 enlisted men.

Blame was laid upon the enemy immediately. Martini’s ‘diary’ alleges that Austro-Hungarian involvement was ‘confirmed’ by the safe-cracking Swiss spy caper. As with the Maine, however, no one has ever produced evidence that the explosion came from outside the vessel. On the contrary, the crew of Leonardo da Vinci was in the very act of loading ammunition when the fire and explosion took place. The Regio Marina deepened their own humiliation by trying to raise the ship and right her again, an expensive and time consuming process that took two years, only for the postwar economic and diplomatic environment to put a kibosh on plans to restore the Leonardo da Vinci. She was scrapped, though her two sister ships were later upgraded for the Second World War.

The Italian part of this story remains a bit opaque to me due to the language barrier and the unfamiliarity with the contextual terrain of Martini’s narrative. His story frankly smells like a fresh cowpie to this writer. If sneaky sabotage actually explains these two explosions, then they are the lone standouts among the genre. Austro-Hungarians never claimed these alleged spywar victories for themselves. Indeed, no sooner had the Italians been disappointed by the war’s outcome than they adopted the alleged tactic of sneaky demolitions against the fledgling Yugoslavian Navy. Rome had been promised a littoral empire in the Adriatic, but they were seeing a new rival created instead, and it was receiving the remnants of the Austro-Hungarian fleet.

Italian frogmen sank the dreadnought Viribus Unitis just after her surrender to the Yugoslavs in 1918. Italian frogmen were still at the cutting edge of this very special mode of warfare in the Second World War, a rare bright spot for their naval ambitions. Perhaps Martini’s dubious tale was in fact the creation myth of a genuine Italian combat innovation? One day I intend to research this story in greater depth, pun intended.

8 - HIRMS Imperatritsa Mariya 1916

Russia was the dominant naval power on the Black Sea in the First World War, but they could not translate that advantage into victory over the Ottomans. His Imperial Majesty’s Ship Imperatritsa Mariya was the first of a class of three battleships armed with twelve 12-inch guns. She would have been a powerful combatant even at Jutland. Of all the cases listed here, however, this one is the most mysterious. According to David Brown and Iain McCallum in “Ammunition Explosions in World War I: A re-examination of the evidence,” a 2001 article in Warship International, this time the ammunition was likely not unstable, so it was probably not responsible for the initital fire.

“On the morning of 20 October 1916, a fire was discovered in the Imperatritsa Mariya's forward powder magazine while at anchor in Sevastopol, but it exploded before any efforts could be made to fight the fire,” they write. Sailors’ fast action flooded the magazines at the cost of their lives. A second explosion near a forward torpedo compartment tore through the flooded compartments and the ship, which had always been heavier in the bow than designed, began to sink bow-first at a list. She capsized over the space of a few minutes and sank in shallow water with 228 sailors on board. “Despite a thorough investigation no explanation has ever been found,” Brown and McCallum write.

Her propellant charges were of pyroxylin (nitrocellulose) with over 12% Pynitrogen stabilised with a small quantity of diphenylamine, and guncotton. Great care seems to have been taken in manufacture and storage, and charges were stowed in steel cases with an asbestos lining. The batch issued to Imperatritsa Maria was made in 1914 and passed tests in January 1915.

It is possible that the magazines were not ventilated well, and that nitrocellulose dust had built up inside them as they were emptied out during gunnery. Accidental sparks and fires could even imaginably happen during the act of re-loading the magazines. Yet the best analysis does not point to spontaneous ignition of the ammunition. “The wreck was salvaged in 1917 and charges recovered from the other magazines,” Brown and McCallum note. “These were examined and there was no sign of deterioration. In 1919 most of these salvaged charges were found safe to use and re-issued.” The ship was raised and scrapped, with two of her guns salvaged for use as coastal defense artillery at Sevastopol in the Second World War.

9 - HMS Vanguard 1917

By this point, experiments had confirmed that large masses of cordite ammunition could experience a rapid build-up of pressure and explode. As early as 1909, a stack of 12-inch cartridges — essentially leather cylinders packed with cordite like spaghetti srands — ignited at the center would be thrown outwards by the one burning cartridge in the middle. US Secretary of the Navy Hiram Maxim wrote of his participation in a 1911 Royal Navy experiment using a stack of loose cordite. "When it was claimed by high officials that English cordite would not detonate, I asserted that it would, providing that the quantity was large enough,” Maxim wrote.

I placed 250 lbs in a light sheet iron case and set it off with a powerful fulminator, and it exploded exactly like nitroglycerine, making a very deep hole in the ground. This experiment was followed by another, conducted by the Government experts, to disprove what I had asserted. They piled up I think two tons of cordite on the marshes of Plumstead and simply lighted it at the top. At first it burnt very much like pitch pine shavings, and then commenced to hiss and flare up; when about half a ton had been consumed, the remainder went off exactly like dynamite, excavating a hole in the soft earth 15 feet in depth and 24 feet in diameter and doing an immense amount of damage to houses in the vicinity.

The problem had clearly matastasized to the dreadnoughts. Exploding battleships at Jutland had confirmed Royal Navy ammunition handling practices, rather than insufficient safety mechanisms, were the biggest threat to the entire battleship. Fireproof doors propped open might as well not exist. “Despite this shortly before midnight on 9 July 1917, more than a year after Jutland, the 19,250 ton battleship Vanguard, at anchor in Scapa Flow, was in a matter of seconds destroyed by three tremendous explosions,” Brown and McCallum write. “Eye witnesses spoke of a white glare between the foremast and A turret with a small explosion followed by two much heavier explosions also with a white glare, the latter taking place in P or Q magazine or both.” She was loaded with the older, unstable ammunition in the exigency of war. Once again, climate control and ventilation did not suffice. “The court of inquiry noted that the cooling in the magazines was not uniform and that some bays were much hotter than others, nor were the temperature readings a reliable guide to maximum temperature.”

There was a potential risk in running electrical leads through magazines. It was learned that empty coal bags had been stowed next to the magazine, so that spontaneous combustion, though unlikely, could not be ruled out. The inquiry revealed that much of the Mark I cordite on board was long past its safe date but Commander Weston, assistant to the Chief Inspector of Naval Ordnance, denied that this posed a direct threat. He refused to answer when asked if in his opinion over-age cordite was dangerous, and declared that there was no reason to suppose that such cordite as had been withdrawn was in an unsatisfactory stage of stability. "It was," he said, "withdrawn in view of the largely increased stocks of cordite of more recent processes which are now available ... it was a clear precaution." Nevertheless vigorous steps were taken to remove large quantities of older cordite from the magazines of the Grand Fleet.

10 - IJN Kawachi 1918

Japan began constructing their own battleships with British assistance, so Kawachi was reasonably similar in form and content to the Vanguard. She was in fact based on the ‘semi-dreadnought’ Lord Nelson class “but without the centre turrets amidships,” R. A. Burt writes in Japanese Battleships, 1897-1945: A Photographic Archive. He notes that Kawachi’s sister ship’s “turret layout was identical with that of HMS Lord Nelson.” Aesthetically, they featured “tall twin tripods and three funnels [which] gave them an appearance not unlike the battlecruisers of the day rather than that of a battleship.” This family of ships was noted for seaworthiness, a primary concern for British naval architects, since their ships were expected to sail the Atlantic gales. They “proved popular in service,” Burt writes.

Even though she was a copy of the British design, the Japanese were justifiably proud of Kawachi. She had been built in Yokosuka Naval Arsenal (established by a Frenchman, Louis-Émile Bertin) and completed in 1912, built “mostly from home-produced materials.”

The guns and mountings, however, came from Britain. Paradoxically, the 12in guns were of different calibres; those of the forward and aft center mountings were 50-calibre, while those of the broadside were 45-calibre. This was a move made to give a shorter gun so that the turrets could be fitted closer together without having to increase the length of the ship to avoid having blast problems or cramped internal conditions. On completion, however, both these problems were still evident in these ships.

A few months after she was completed in 1912, Kawachi was alongside the Mikasa and able to dispatch fire control parties to assist when a sailor on board the now-obsolete hero ship started a fire in the forward magazine. She later saw action in the 1914 bombardment of Tsingtao, the German colony in China. “On 12 July 1918 Kawachi suddenly blew up at anchor as a result of an internal explosion, very similar” to other recent battleships going kaboom in harbor. “A court of inquiry established that it was almost certain that a spontaneous ignition of unstable cordite was to blame, even though it had been kept in airtight lockers,” Burt concludes. Indeed, it was the very airtightness of the compartments, designed to protect the ammunition from enemy action, that turned the spontaneous ammunition fire into an explosion, and that armored compartment into a bomb, much like a giant pipe bomb. The British had watched it happen in 1909. It was still prone to happen.

Peace intervened. Every navy was cut back, old ships were scrapped, and a treaty to limit the exhausting, expensive battleship race was signed by all parties. The old ammunition, heat control, and corner-cutting practices passed away into history.

11 - SPS Jaime I 1937

The Spanish Armada was a shade of its former self after defeat by the upstart American empire. Turning to their most famous historical enemy for help getting back up on their sea legs, Spain built two dreadnoughts without superfiring turrets. Like the Japanese, the Spanish construction program used as much local material as possible. Construction was nevertheless delayed by the war, as Britain was keeping all the guns and turrets for the needs of their own battlefleet. London had cornered the battleship market and so war disrupted their supply chains to customers. Completed at last in 1921, and named for the 14th century king, Jaime I would have been a world-class vessel if completed on time. Her service lasted throughout the Great Depression and she would have been modernized if not for the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

She was a scene of early contention in the conflict. According to Francisco J. Romero Salvadó’s Historical Dictionary of the Spanish Civil War, Spanish naval minister José Giral “appointed loyal telegraph operators at the headquarters in Madrid, such as Benjamin Balboa, an auxilliary officer who intercepted a message from General Francisco Franco to the insurgents in Spanish Morocco. These operators alerted the crew aboard the battleship Jaime I, who then mutinied against their officers and kept control of that battleship” along with other vessels in the harbor. However, naval power did not do much for the Republican cause. “Shortages of fuel and the limited expertise of the crews impeded the imposition of a tight blockade in the Strait of Gibraltar, while attacks by enemy aircraft sowed widespread panic.” Fascist air power served the Nationalist cause. Italian bombers attacked the Jaime I in Cartagena in May 1937, scoring hits that disabled her. Four weeks later, a fire and explosion destroyed the ship, killing over 200 sailors. Refloated two years later, she was scrapped.

Although no board of inquiry confirmed the cause, it is likely that crew indiscipline played a role. Cigarette smoking may figure in some of these incidents, and this is perhaps the example of a battleship exploding from within in which that particular scenario seems most likely. With the ships being run by sailors’ committees until September 1937, conditions on board were perhaps anarchic, like the international leftists fighting fascism on the Spanish mainland. We will never know for sure. By the time she was built, experiments had long shown that ammunition fires could smolder for hours before detonating. A single ash from a single smoker was enough. Another possibility is electrical short, a problem that could easily be missed by a crew that is not performing their normal duties. Jaime I is likely evidence of the importance of the human factor in all of these incidents.

12 - IJN Mutsu 1943

Commissioned in 1921, Mutsu was intended to make Japan one of the world’s great naval powers. “During 1916 eight battleships and eight battlecruisers were planned, and experience gathered from the Royal Navy during the conflict was utilized in the designs,” Burt writes. Adopting the new British design practice of superfiring turrets fore and aft, Japan laid Mutsu down in 1918 but suspended construction during the Washington Naval Treaty negotiations.

As a result of the talks, six major Japanese units were scrapped and it was suggested that these two might follow. The Japanese bluntly refused as they knew the US Navy was building ships armed with the same calibre. In the end the day was won and [her sister ship] Nagato took to the water in 1920 as the first seagoing battleship with 16in guns.

Her true speed was kept secret. Upgraded in the 1920s, her funnel was re-shaped and her pagoda mast added. This eye-catching feature made Japanese battleships recognizable at a distance, indeed it is a compelling example of how every nation that built battleships incorporated a national aesthetic. Burt writes that “during construction” they “caused serious concerns regarding stability” but “in fact, the stability of Japanese warships was good.” When the constructor, Hiraga Yazura, tried to retire, then Japanese battleships did experience stability issues. Personal touch can never be entirely removed from the design process.

Along with the new mast in 1927, the 1936 refit added more armor, torpedo defense bulges, and technology. Yet it was no protection when Mutsu detonated while at anchor in Hashirajima fleet anchorage at Yamagushi. The explosion shortly after noon in the magazine of turret three made her “split in two … with the forward part (and superstructure) capsizing and sinking immediately,” according to Burt. “The aft part, however, remained afloat until the next day having shown remarkable resistance to sinking.” He notes that a cousin of the Mutsu, the Fuso, sank in the same fashion after taking 16-inch fire from a line of American battleships in the Surigao Strait in 1944. “The news of the loss was kept from the general public until after the war,” he writes. There were 353 survivors from the 1,474 sailors on board; they were scattered throughout the fleet to keep the secret of her destruction.

At first, the anchorage was searched fruitlessly for American submarines. Potential acts of sabotage were considered and the preliminary report blamed “human interference” as the most likely cause. The Japanese Type 3 anti-aircraft shell, an incendiary device designed to be fired from the main guns, came under suspicion and was removed from service. However, testing could not confirm a problem existed with that ammunition. Japanese battleships also had a reputation for incorporating much more flammable material, such as wood furniture, out of cultural habit, and of course all the wiring and re-wiring meant that any fault might set fire to insulating material. Whatever the cause, the admiralty was determined to raise and rebuild her, sending divers down over several months of investigation, until a minisubmarine crew was lost while diving the wreck to salvage her. With their ships thirsting for fuel oil, divers cut into her bunkers and pumped out 580 tons of it for a naval operation. Salvage efforts finally succeeded in 1970. Her main guns and turret were put on public display afterwards.

The dogs that didn’t bark

Altogether, the ships listed here represent about three percent of all the battleships ever built. This survey has managed to find an exploding battleship under almost every flag that sailed one during the period under study. Setting aside the battleship race in South America, which featured British and American-built vessels but only in very small numbers, as well as the relatively small Austro-Hungarian fleet, none of whom can represent quite the same ‘sample size’ of battleship fleets as the ones listed here, one nation surely stands out as being accident-free: Germany.

A full analysis of the German battleship, naval regulations, and crew drill is beyond the scope of this essay. Some suggest that Germans are culturally inclined to be more rigorous about safety devices and rules, but this is quite difficult to detect as history. “It is unlikely that a definitive answer will ever be given to the question why so many ammunition explosions occurred in British, Japanese and Italian ships, and so few in German ships,” Brown and McCallum write. However, their analysis finds only one explanation that makes sense. “One of the few essential differences between the British and Allied ships and their German opponents lay in the fact that while the former filled their shells with picric acid-based high explosives whether in the form of lyddite, melinite or shimose, all of which detonate at temperatures above 300degC, the latter relied on the inert and therefore much safer TNT,” they write. “Can it be purely coincidental that almost without exception the ships destroyed by massive explosions were carrying shells filled with picric acid-based explosives?”

Although historians can never be sure, the authors “believe that while they are unlikely to have been a primary cause of explosions, picric acid-based shells may on occasion have turned an accident into a disaster.” The British Admiralty seemed to think so, for “in 1918 lyddite was replaced altogether by the less sensitive high explosive 'shelite,’” the authors note. “Support for this hypothesis comes from the low order cordite explosions in [other vessels] which in all probability were not carrying lyddite.” Rather than German character, the Imperial German Navy’s choice of older, safer, less explosive ammunition seems to have kept them off this dubious list. Such are the ironies of history.