A Very Old Crow Reacts To The Brand-New US Army 'Terrestrial Layer System'

Tactical SIGINT/EW in the 21st Century

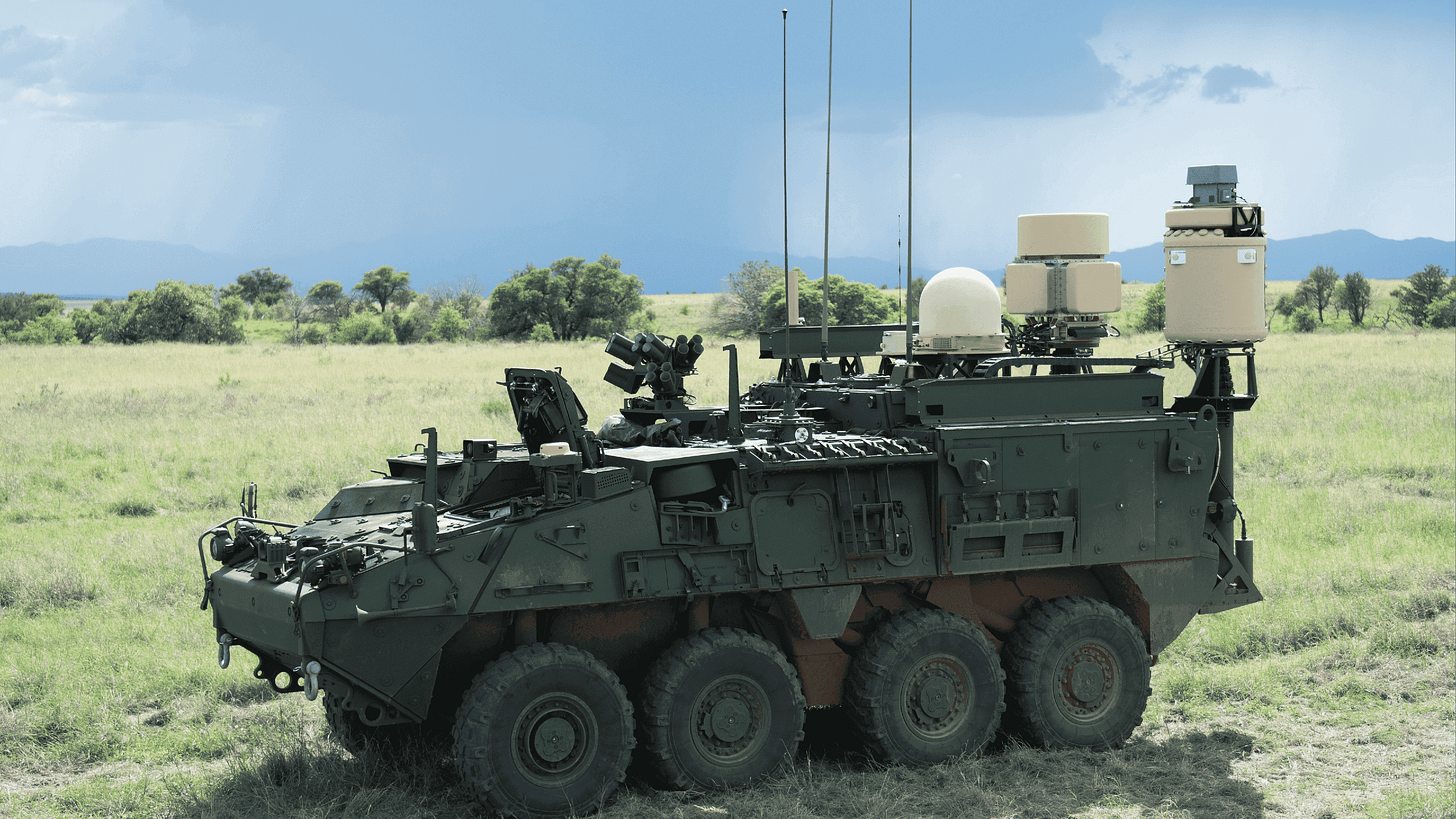

It has wheels, at least. Too many wheels, if you ask me. But at least it has wheels.

Not that anyone has asked me, because I am just a “Raven” or “Old Crow” from the 1990s-era of US Army tactical signals intelligence and electronic warfare (SIGINT and EW), not a defense consultant.

To be clear, I have not la…