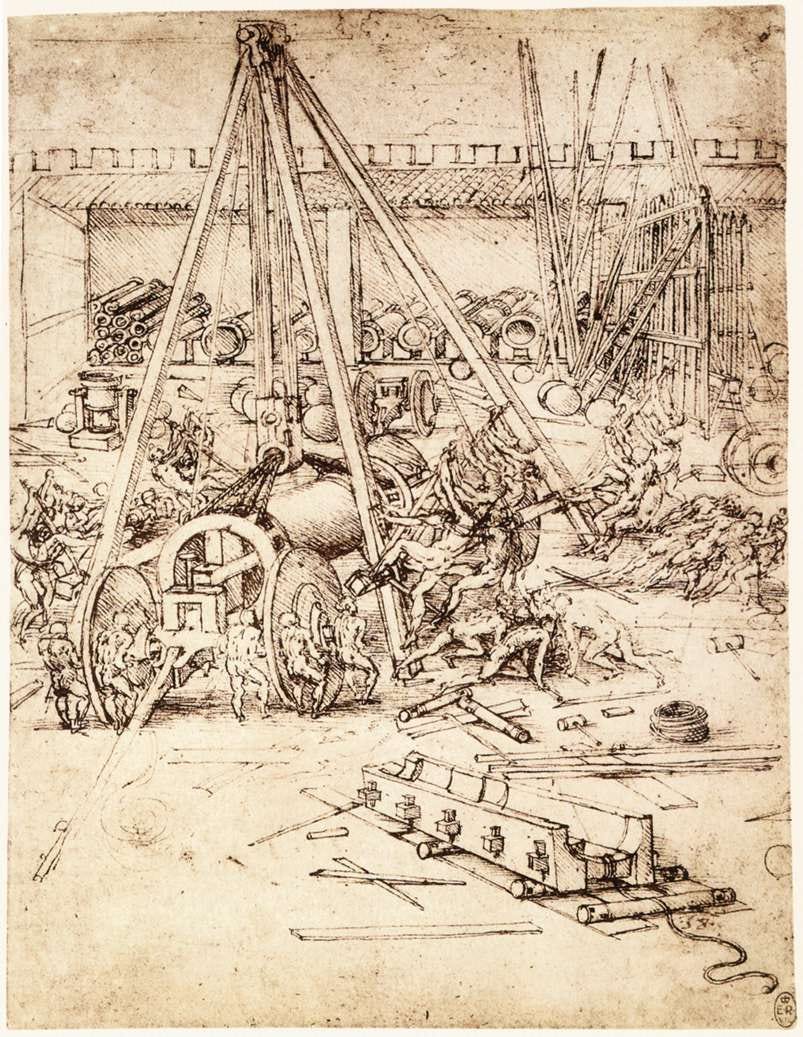

There is a bombard on the left, inside the door of the shed, and cannonballs sized to fire from it. Already obsolete, its presence in this sketch by Leonardo da Vinci, the world’s most famous Renaissance man, seems a comment on the technological changes to artillery in his day. We are observing a military revolution in progress with da Vinci. Our visual tour of the image begins with this reference to what has been replaced by the thing at the center of the picture, the primitive terror weapon which gave us the word bombardment.

This view is titled Cannon Foundry, but it depicts the arsenal, not the manufacturing area. At the very top of the image are crenellations which might be stylistic, and not a real battlement for serious defense, for the shed with the terra cotta roof is apparently built against the wall, and there is no visible platform on the wall for fighting behind the merlons. Form already lacks functionality in Milan, where da Vinci inked this drawing. The cannons will make the wall’s form entirely obsolete.

Inside the shed is a row of cannon tubes made in the Ottoman style, which is to say the style of the Italian artillerists who made the first Ottoman cannons. At center, behind the crane in the middle, stands a caisson for the giant cannonballs, which are also positioned along the front of the shed. This ammunition was not made of iron yet. Instead, during these days of early gunpowder artillery, masons hewed the cannonballs from stone.

Each caisson transported one huge stone ball. When the rate of fire was a single digit number of shots per day, this inefficiency did not matter so much. Sending such a cannon to war was a major production, as da Vinci seems to be pointing out, here. First, the storage sled would be moved out on wooden rollers bound in metal, as seen in the foreground. Then the tube section would be lifted off the cradle using a crane equipped with a pulley, as seen in the center of the image.

The cannon tube section here is being limbered for transport, that is, made ready for war. A wooden support structure inside the tube is being fitted to a rather substantial wheel axle with a very long hitching pole, since these guns needed teams of sometimes hundreds of horses or mules to transport. The key takeaway I think da Vinci wanted us to have is the amount of human labor involved in mobilizing a cannon in 1487, when they were enormous — and extremely inefficient.

There are perhaps thirty men altogether in the scene. There are four teams using levers to winch the cannon tube upwards, a team of four men on the right hauling on a rope to lift the mouth of the tube onto the axle assembly, which has six men rolling it forward. All this dangerous choreography would never pass a modern federal workplace safety inspection. It was dangerous, demanding work that needed lots of experienced men. And this was just getting the gun tube out of the arsenal.

Once the gun was out of the arsenal, it would be transported to its destination by boat, if at all possible. In fact, watercraft was usually the only possible way to transport such a heavy object, as most roads and bridges were not built to support it. These cannons were most often placed onto the foredecks of galleys, again using cranes, laying on cradles very like the storage sleds seen here. Cannons were still manufactured to mount on either ship or wheeled land carriage, being swapped from one to the other and back again with relative ease, until the 20th century.

Once it arrived at its firing point — either on the deck of a galley or outside the walls of Vienna — two tube sections would be screwed together using levers inserted into the ‘squire holes’ around the rim of the tube section. The resulting seal was hardly perfect, and there were infamous examples of gunners and their crews being killed by barrel explosions. If the payoff does not seem worth all this struggle and risk, perhaps that is how da Vinci felt, too.

Leonardo da Vinci was still alive in 1499 when Louis XII of France invaded and began the Italian Wars by blasting his way through medieval city walls with cannons. At the time he died in 1519, the first signs of a new defensive architecture incorporating and replacing the old one had appeared in Italy. Known as the trace Italienne, it used earthen ramparts to absorb cannonball impact, ditches and earthworks to funnel attackers into zones of defensive artillery fire, and outworks to flank attackers with cannons.

Crenellations like the ones in da Vinci’s drawing were already obsolete. Whenever you see them on castles and other buildings built after 1700 — for example, your local university ROTC building, or Windsor Castle, where this ink drawing hangs — they are entirely decorative, never really defensive. Da Vinci sketched a transitional moment during a military revolution.

In military-historical terms, the most revolutionary detail in this drawing is almost lost at the upper limit of the background of the composition. It is the wall feature, the battlement ‘teeth’, an invention that is thousands of years old, being rendered obsolete by the technological progress happening at such great effort in the foreground of the sketch. Man achieves, and then overcomes his own achievements.

I have a little less time for this website than I used to, so I have lowered the subscription price. Grab this opportunity to save on access to premium content like this essay, published last week:

How Pancho Villa Lost His Aura Of Invincibility

Legend has it that Col. Maximillian Kloss, an Austrian-born German immigrant to Mexico, offered his services to Pancho Villa in an El Paso hotel bar in 1913 as the teetotaling warlord sipped a strawberry soda, his favorite. In exchange for his military expertise, Kloss wanted Germany to have basing rights in Mexico. The offer never came to fruition, and perhaps history hinged on Villa’s failure to follow up. For when the two men met again in 1915, Kloss was serving Villa’s enemy, who put his expertise to use and shattered the army that Villa brought to bear.